"Join us!" --the trees in Evil Dead

A major theme to emerge from my current seminar on the nonhuman is the distinction between apophatic nonhumanism and cataphatic nonhumanism. Since these terms don't seem to come up that often in contemporary discussions I figured it would be useful to lay it out here.

The nonhuman is an especially active topic today, as it overlaps with so many important fields of inquiry, from climate change and animal studies, to media archaeology and the turn in media studies toward infrastructure. Of course objects and things have long been at the center of conversations in critical theory, from Marx's inspection of the commodity form, to psychoanalytic theories of the object. I'll also point out the interesting work being done at the Sensory Ethnography Lab, including the astounding 2012 film Leviathan, which may be the best exploration of nonhuman perception that I've ever seen. Speculative realism too has its interest in the nonhuman, that being the crux of the critique of correlationism, or at least as I interpret it. And certainly the largest discourse on the nonhuman comes from theories of the subject, broadly conceived, including examinations of the not-quite-human (the proletarian, the child), the sub-human (the colonized, the leper, the schizophrenic), the post-human (cyborgs, queerness, Afro-futurism, Prometheanism), and the generic person (the common, the whatever).

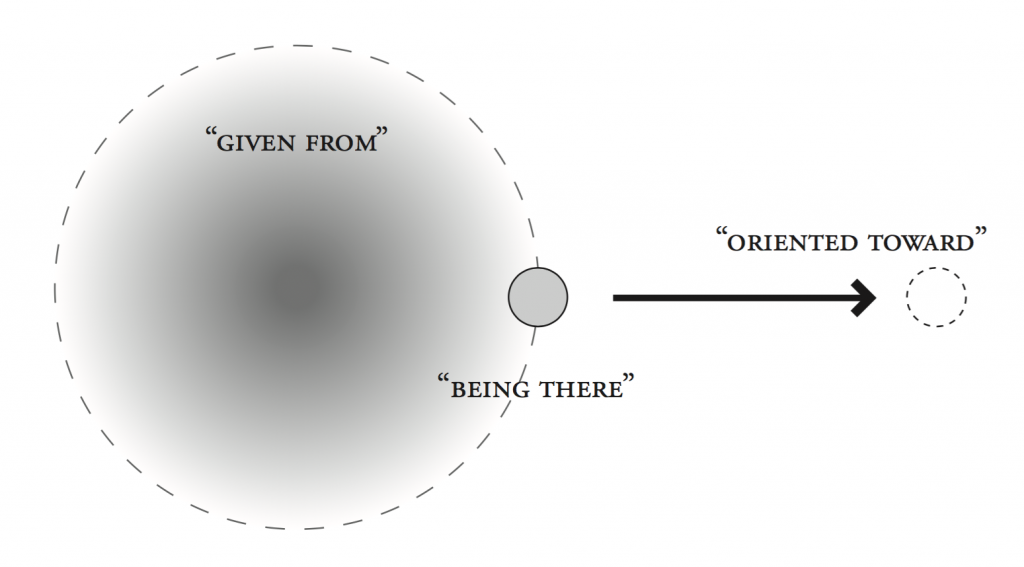

Through all this, one truth emerges: the question of the nonhuman is an exceptionally difficult one. The question often bumps up against the very limits of philosophical method. What does it mean to be? What does it mean to know? Often such questions are prefigured precisely in human terms, making the question of the nonhuman practically incompatible with intellectual inquiry as we understand it. And at the same time the category “human” is often predefined, either overtly or covertly, in ways that bar admittance to certain kinds of subjects, putting the very integrity of the term “nonhuman” in doubt. At best we're wildly speculative in our conclusions about nonhuman entities like animals, plants, machines, or physical matter. At worst we sadistically ascribe our own special qualities to them, through a kind of boundless colonial expansion.

In short, to query after the nonhuman is to confront the symbolic apparatus--the language itself--that defines the human, and keeps the rest silent. “I have not tried to write the history of that language,” wrote Foucault in his first book, “but rather the archaeology of that silence.” Continue reading →