I am happy to be included in Informatics of Domination, just recently published. Each contributor's task was to comment on a pair of terms from Donna Haraway's famous informatics of domination chart from 1985. Each contributor could also opt to propose a third term. I wrote on Haraway's two terms perfection and optimization, adding a third term, absolution. Thanks to Zach Blas, Melody Jue, and Jennifer Rhee for putting the volume together.

Perfection, optimization, and absolution are all terms that originate in moral and metaphysical discourse. Something may realize itself, it may be guided or adjusted, and it will eventually unloosen and dissolve. Perfection refers to something having been fully accomplished, to something in a state of completion. From a Latin root verb meaning “to make,” perfection entails a process of production. To perfect something is to intervene positively in its development, to push it in a particular direction, to craft it and finish it and make it shine. Perfection connotes maturity, development, flawlessness, purity, completion. In this sense, perfection will always have a target in its sights, the target of the ideal form. The perfect soul, or the perfect body, or the perfect society—all these things must be built and polished and pushed toward whatever ideal has been determined (the ideal soul, the ideal body, the ideal society). A metaphysical logic is particularly legible here; the developmental goal or end is the thing that most characterizes perfection, over and above the particular quality of the goal.

Perfection, optimization, and absolution are all terms that originate in moral and metaphysical discourse. Something may realize itself, it may be guided or adjusted, and it will eventually unloosen and dissolve. Perfection refers to something having been fully accomplished, to something in a state of completion. From a Latin root verb meaning “to make,” perfection entails a process of production. To perfect something is to intervene positively in its development, to push it in a particular direction, to craft it and finish it and make it shine. Perfection connotes maturity, development, flawlessness, purity, completion. In this sense, perfection will always have a target in its sights, the target of the ideal form. The perfect soul, or the perfect body, or the perfect society—all these things must be built and polished and pushed toward whatever ideal has been determined (the ideal soul, the ideal body, the ideal society). A metaphysical logic is particularly legible here; the developmental goal or end is the thing that most characterizes perfection, over and above the particular quality of the goal.

Similarly, optimization refers to the most favorable state. The word is derived from a root meaning “best.” Yet optimization is more sober and pragmatic than perfection. Universals matter less here; identities are not determined in absolute terms, but rather provisionally, nominally. Ignoring thorny questions about essence or purity, optimization means playing the cards as they lay, making the best use of one’s predicament, whatever it may be. If perfection is theological in spirit, always aspiring to some higher end, optimization tends to be more stubbornly secular and mundane. The best is not eternal, or essential, and certainly not given by God, even if kings and elites try to claim divine authority. Rather, the optimal is simply one arrangement among others. The optimal is the most efficient organization, the most pleasing assemblage, or the most suitable configuration. Continue reading

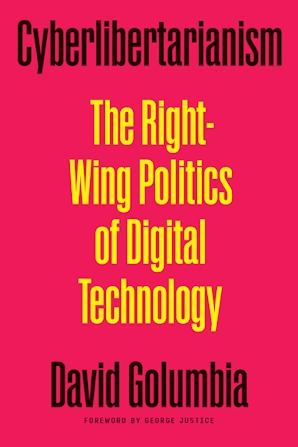

Does disorder have a politics? I suspect it must. It has a history, to be sure. Disorder is quite old, in fact, primeval even, the very precondition for the primeval, evident around the world in ancient notions of chaos, strife, or cosmic confusion. But does disorder have a politics as well? As an organizing principle, disorder achieved a certain coherence during the 1990s. In those years technology evangelists penned books with titles like Out of Control (the machines are in a state of disorder, but we like it), and The Cathedral and the Bazaar (disorderly souk good, well-ordered Canterbury bad). The avant argument in those years focused on a radical deregulation of all things, a kind of full-stack libertarianism in which machines and organisms could, and should, self-organize without recourse to rule or law. Far from corroding political cohesion, as it did for Thomas Hobbes and any number of other political theorists, disorder began to be understood in a more positive sense, as the essential precondition for a liberated politics. Or as the late David Golumbia writes in Cyberlibertarianism, the computer society of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries culminated in “the view that ‘centralized authority’ and ‘bureaucracy’ are somehow emblematic of concentrated power, whereas ‘distributed’ and ‘nonhierarchical’ systems oppose that power.” And, further, Golumbia argues that much of the energy for these kinds of political judgements stemmed from a characteristically ring-wing impulse, namely a conservative reaction to the specter of central planning in socialist and communist societies and the concomitant endorsement of deregulation and the neutering of state power more generally. Isaiah Berlin’s notion of negative liberty had eclipsed all other conceptions of freedom; many prominent authors and technologists seemed to agree that positive liberty was only ever a path to destruction. Or as Friedrich Hayek put it already in 1944, any form of positive, conscious imposition of order would inevitably follow “the road to serfdom.” Liberty would thus thrive not from rational order, but from a carefully tended form of disorder.

Does disorder have a politics? I suspect it must. It has a history, to be sure. Disorder is quite old, in fact, primeval even, the very precondition for the primeval, evident around the world in ancient notions of chaos, strife, or cosmic confusion. But does disorder have a politics as well? As an organizing principle, disorder achieved a certain coherence during the 1990s. In those years technology evangelists penned books with titles like Out of Control (the machines are in a state of disorder, but we like it), and The Cathedral and the Bazaar (disorderly souk good, well-ordered Canterbury bad). The avant argument in those years focused on a radical deregulation of all things, a kind of full-stack libertarianism in which machines and organisms could, and should, self-organize without recourse to rule or law. Far from corroding political cohesion, as it did for Thomas Hobbes and any number of other political theorists, disorder began to be understood in a more positive sense, as the essential precondition for a liberated politics. Or as the late David Golumbia writes in Cyberlibertarianism, the computer society of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries culminated in “the view that ‘centralized authority’ and ‘bureaucracy’ are somehow emblematic of concentrated power, whereas ‘distributed’ and ‘nonhierarchical’ systems oppose that power.” And, further, Golumbia argues that much of the energy for these kinds of political judgements stemmed from a characteristically ring-wing impulse, namely a conservative reaction to the specter of central planning in socialist and communist societies and the concomitant endorsement of deregulation and the neutering of state power more generally. Isaiah Berlin’s notion of negative liberty had eclipsed all other conceptions of freedom; many prominent authors and technologists seemed to agree that positive liberty was only ever a path to destruction. Or as Friedrich Hayek put it already in 1944, any form of positive, conscious imposition of order would inevitably follow “the road to serfdom.” Liberty would thus thrive not from rational order, but from a carefully tended form of disorder.