(I started researching the material below in 2018 and had mostly given up for lack of success in confirming the historical sources. Yet considering the times we live in, it seems relevant and necessary to pass along these fragments and unfinished investigations in the hopes that someone else might undertake a proper study of Vincent Hollier, who by all accounts was an interesting fellow and an important pioneer. I was able to make email contact briefly with Hollier in early summer 2020, yet he didn't respond in depth to my interview queries and I decided not to pester him further. Hollier passed away last month at the age of 77.)

First, the basic coordinates. Anthony Wilden published a book in 1972 called System and Structure: Essays in Communication and Exchange. A lost gem that few people read anymore, System and Structure is an unclassifiable cocktail of cybernetics and continental theory that contains one of the first significant philosophical reflections on the digital and the analog.* Wilden's book would go on to influence another key text in this discourse, "Shame in the Cybernetic Fold" by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Adam Frank. In fact I first learned of Wilden's book by reading Sedgwick and Frank's essay.

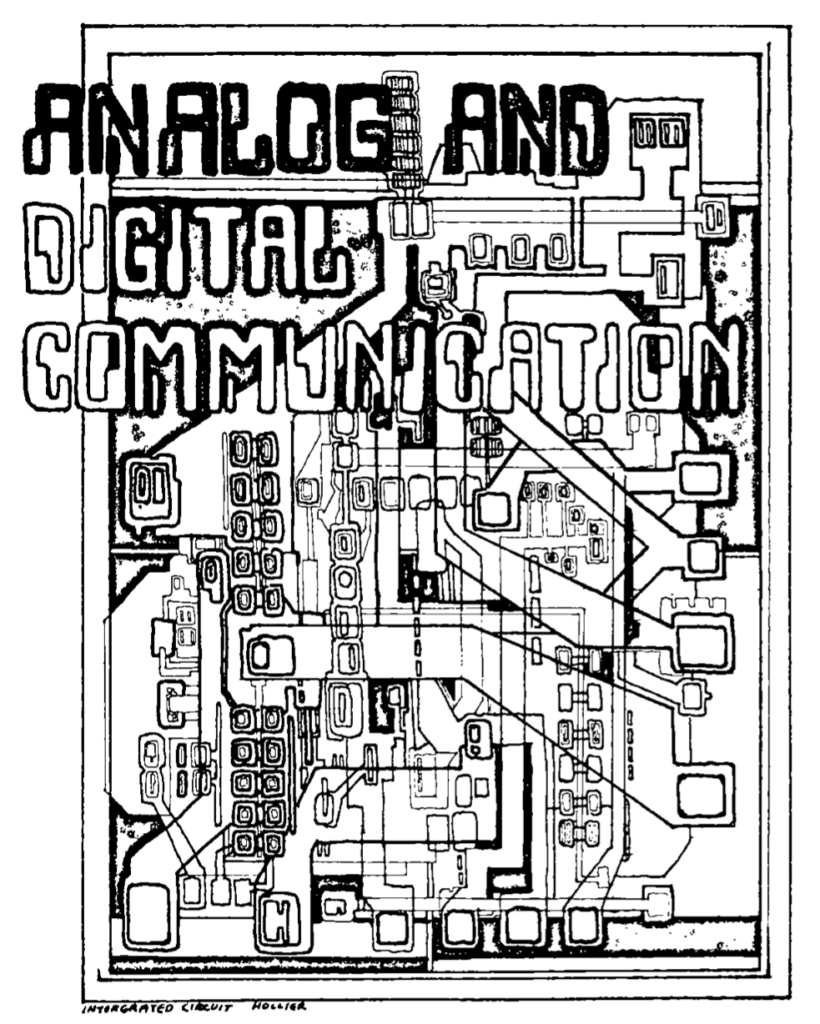

Now the important part: Inserted as an appendix between chapters seven and eight of System and Structure is a six-page graphical essay by one Vincent Hollier titled "Appendix II: Analog and Digital" (196-201). Hollier's appendix is significant because it is one of the earliest instances of Digital Studies composed by an African American.

My colleague Charlton McIlwain has written on the history of African Americans and computing in his book Black Software, extending that history earlier than one might expect, while also undoing the notion that Black Americans were mostly non-participants in computer history. Perhaps the story of Vincent Hollier might add another page to that history. Is Hollier's the first work of Black Digital Studies? I'm no historian. And certainly the quest for origins is a fruitless endeavor, if not also politically suspect. Regardless, Hollier's graphical essay is doubtless an important early contribution from an era with a relative paucity of archival sources.

Hollier was a militant presence on the UC-San Diego campus during college. He wrote a few articles in the university newspaper Triton Times, including an article from April 2, 1971 titled "Beyond Racism." In the text, Hollier articulated a vivid critique of whitness: "People are sick of this philosophy of limits that the vast majority of the white race has embraced. I know Blacks are sick of it. Data Banks, smog-burning the lungs, pigs on a shooting spree, that almighty dollar, protective reaction, 'law and order,' UCSD, no-knock laws, all this and more can be traced right on back to that white way of living, that's not living." Note Hollier's reference to "Data Banks," evidence that he was cognizant of the technological universe newly emerging in those years.

I don't have much information about when or how Hollier and Wilden first met. Wilden taught at UCSD from 1968 to at least 1972. And Hollier attended college at UCSD during those same years. As Hollier relayed to me via email: "Assembling that essay [for Wilden's book] may have occurred when I was associated with Professor Jef Raskin at UCSD." So it seems likely that Raskin, the pioneering computer scientist and artist who would later work at Apple, originally put Hollier and Wilden in touch. Although I don't have any sense that Hollier and Wilden collaborated in any substantive way beyond the publication of System and Structure. I also have no information on the material conditions of the collaboration. Was Hollier paid for his contribution? Did he receive any royalties from the publication of System and Structure? By Wilden's own admission, Hollier developed the illustrations on his own, without Wilden directing him what to create. So did Hollier's graphical essay influence Wilden's own thinking in the book? Hollier clearly had a solid knowledge of math and technology, so it makes sense that Wilden might have adopted some of Hollier's ideas. I simply don't know the answers to these questions. Either way, Hollier stands as a kind of liminal partner in Wilden's theory of the digital and analog, at once foregrounded but still also marginalized.

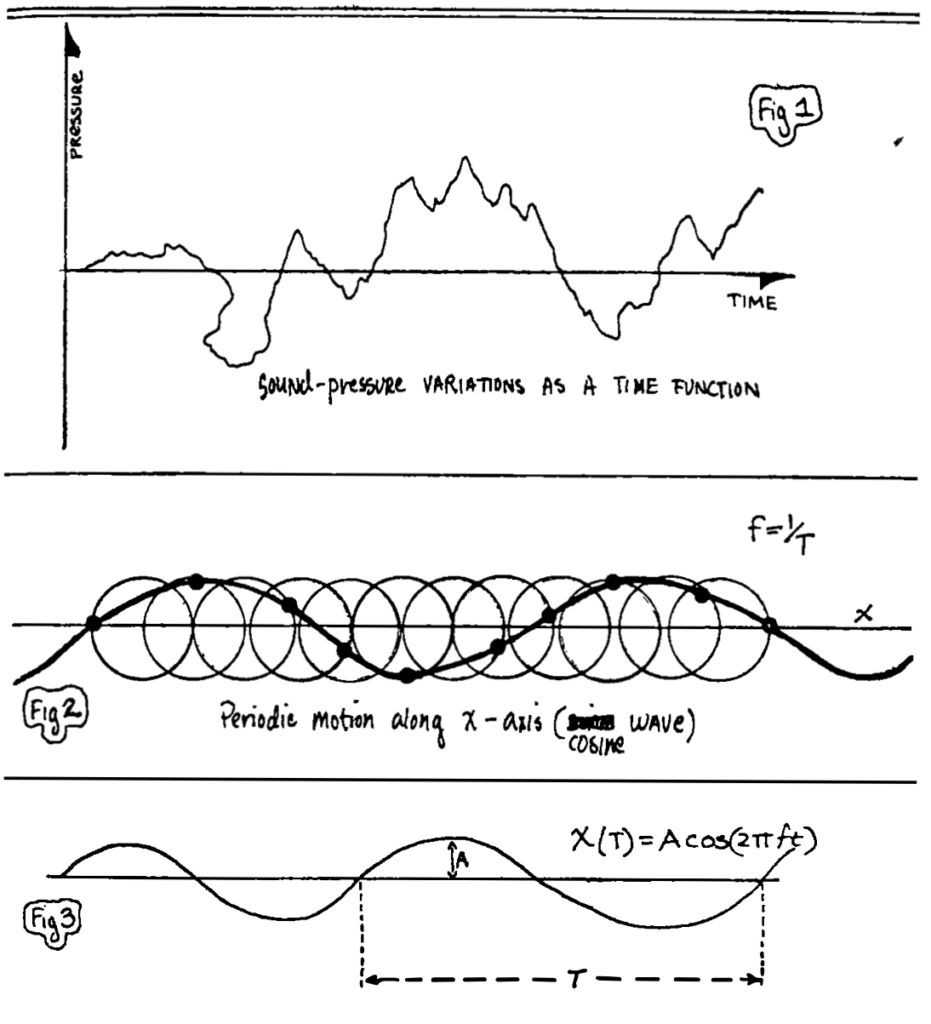

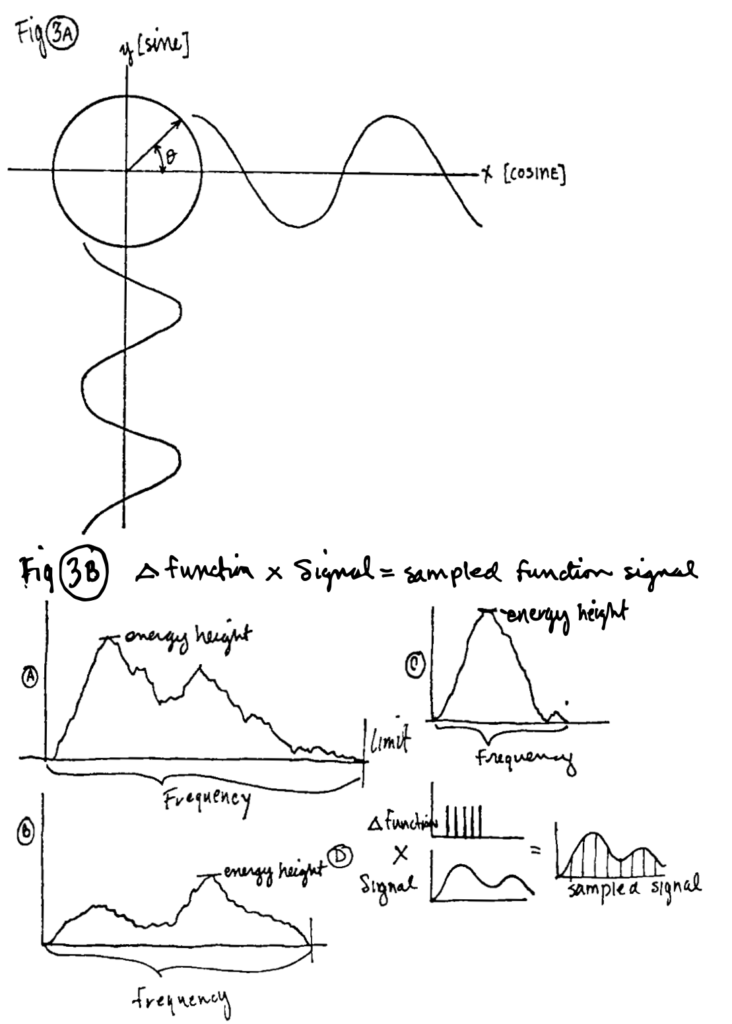

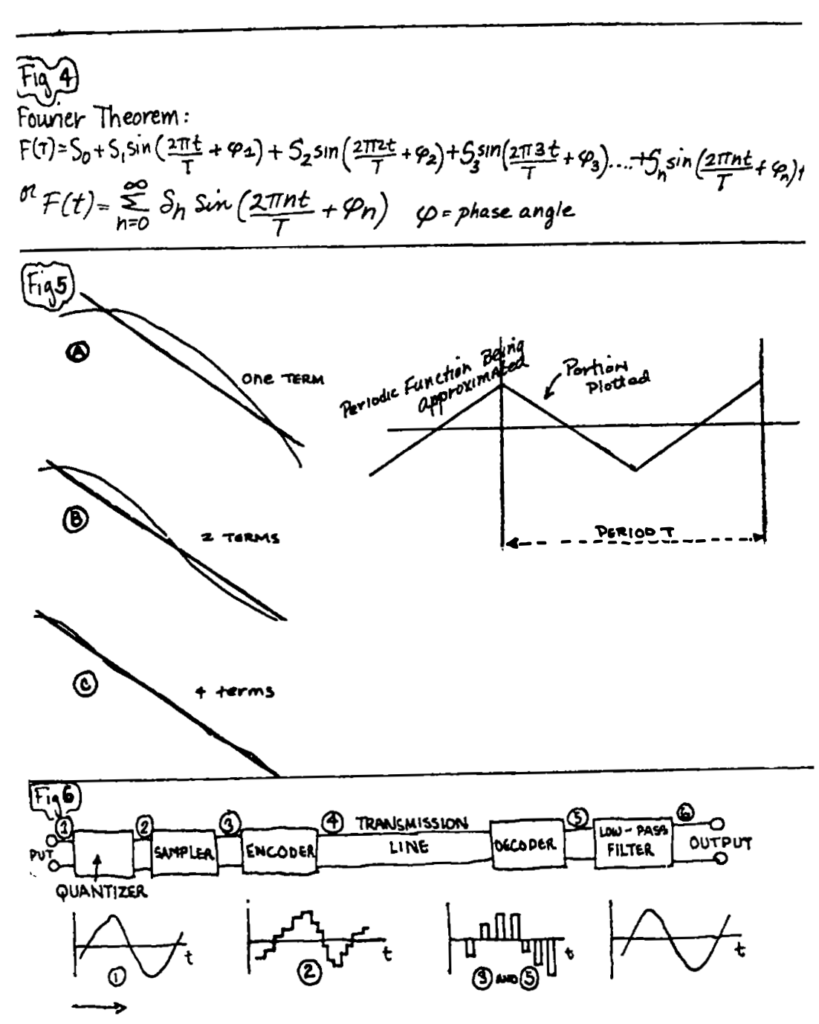

Let's walk through Hollier's graphical essay. He starts with an illustration of an integrated circuit under the heading "Analog and Digital Communication" (shown above), then moves to drawings of wave movements, a diagram on analog-to-digital encoding and decoding, formulas by Joseph Fourier, culminating with a drawing depicting "levels of consciousness" spanning the "neurophysiological excitation" of small molecules up to the macro level of the human mind.

(Regarding the question of genre: Hollier's essay is not prose, but rather consists mostly of hand drawings -- charts and diagrams -- along with text annotations. It is not an essay in the proper sense, but more like a graphical study. Still, I'm comfortable calling this an "essay," since I think it's important to keep a broad mind about the format that this type of work should take.)

Hollier's first three illustrations explore analog phenomena, specifically different kinds of time functions. The first represents something akin to a sound wave, with "sound-pressure variations" indicating the changes in amplitude that accompany a complex wave shape.** Figures 2 and 3 (along with 3A below) describe simple harmonic oscillation, specifically how rotational motion can also be described as a wave form along the time axis.

Figure 3B is somewhat ambiguous, however Hollier appears to be illustrating a group of frequency-domain graphs of signal magnitude (labeled "energy height"), in order to illustrate the Fourier Transform. What Hollier calls "Δ function" is likely a reference to the Dirac delta function, an important component in waves after they have been transformed from the time domain to the frequency domain. (Let me observe somewhat gnomically that the Fourier Transform is one of the great moments in which the analog bridges over to the digital; Hollier seems to have understood this already some 50 years ago.) Figure 4 punctuates the previous figure by providing the mathematics behind the Fourier series for a periodic signal.

Figure 5 shows how continuous functions may be most effectively plotted (or sampled) based on the length of a period. The so-called Nyquist-Shannon Theorem states that the sampling rate must be at least twice the maximum frequency present in the signal, else the signal will be degraded. Hollier doesn't mention Harry Nyquist or Claude Shannon here, although one may assume that's what he was thinking about. With Figure 6, Hollier shifts into describing the process of digital communication itself. The illustration is a more technical version of Shannon's famous "Schematic diagram of a general communication system."

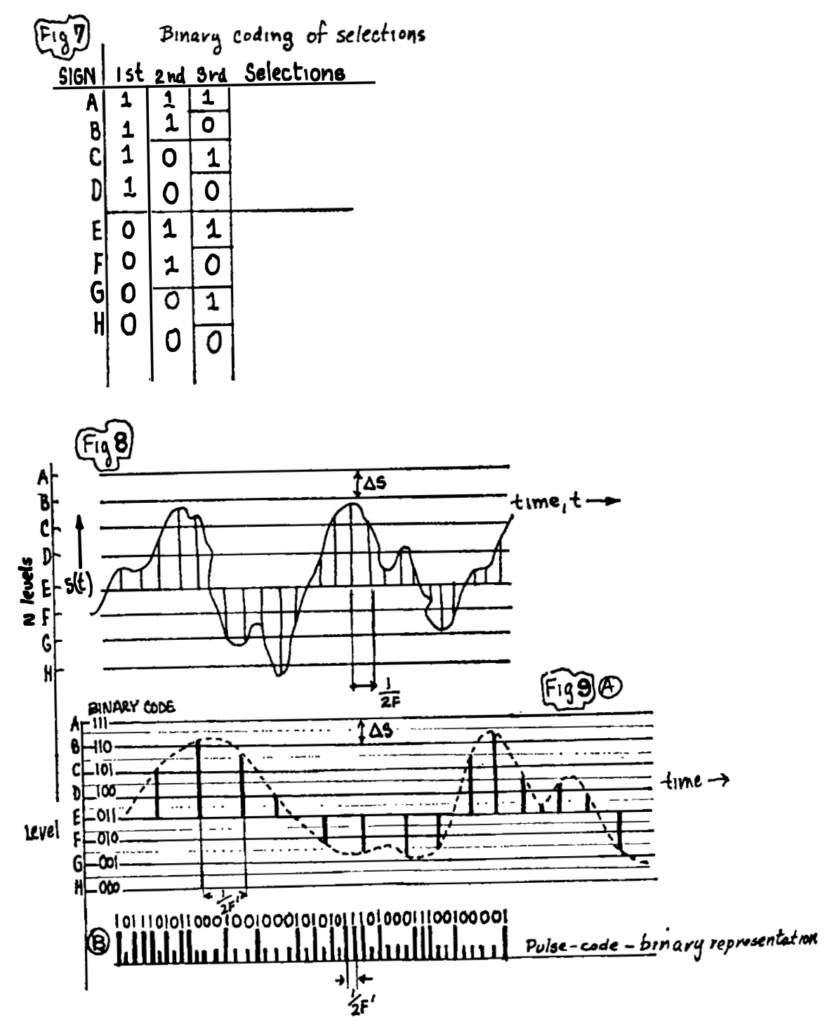

These figures show how a sampled analog signal can be encoded into a string of zeros and ones. First, a look-up table is composed to match binary numbers with letters (signs). Then Hollier shows how the wave is sampled, its height measured and matched with the corresponding binary code from the look-up table, resulting in a serial string of all the binary codes arranged in linear order.

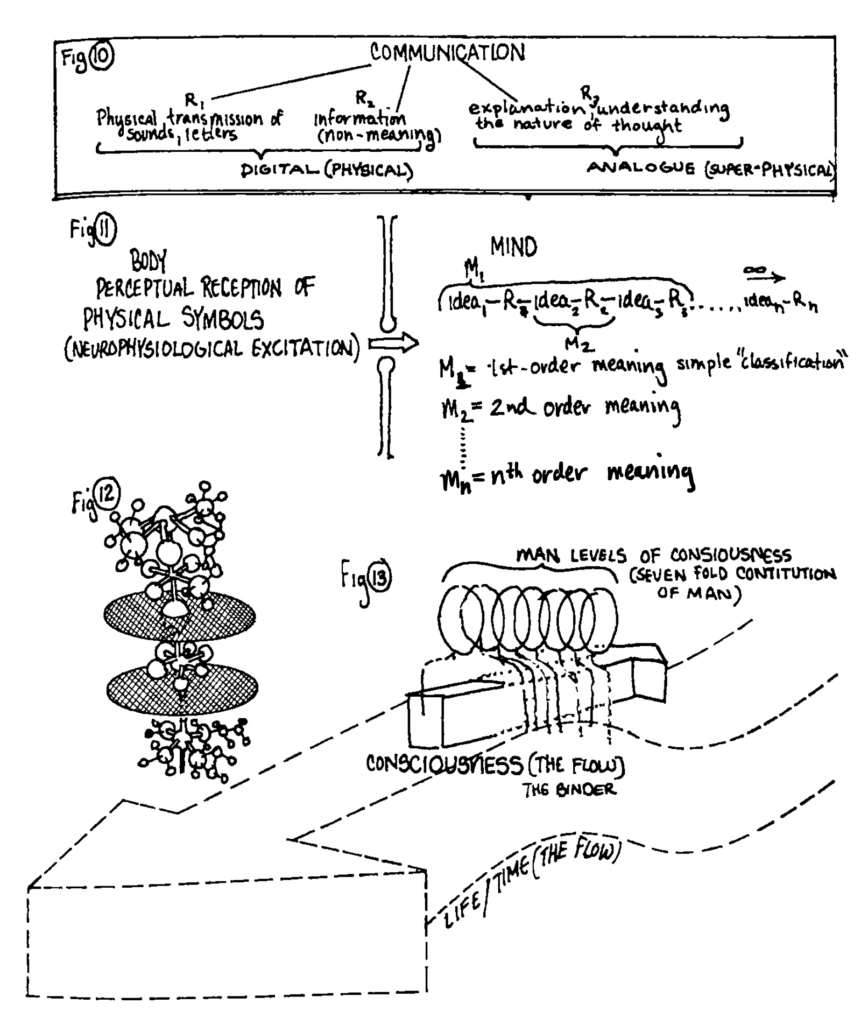

Hollier's last four figures are the most speculative of the whole project, and in a sense the most satisfying. These are philosophical diagrams first and foremost. I wondered initially why Hollier labeled the analog as "super-physical" in Figure 10. A common sense understanding of the analog puts it on the side of the real, closer to the continuousness of material reality. Yet here Hollier placed it firmly on the side of meaning and (higher) value, assumed to be "super-physical." At the same time, the digital consists of merely physical phenomena, understood across two aspects, the discrete symbols themselves in their physical inscriptions, along with (a very Shannonite) notion of meaning-agnostic information. I'm not sure this means Hollier was a Digital Philosopher -- the label given to those who claim that physical reality is digital -- yet he does promote a fundamental association between the physical and the digital.

Figure 11 reiterates a mind-body duality, common in Western philosophy, except Hollier supplements the duality with a specifically technical veneer. The body receives "neurophysiological excitation" from symbols, and the mind is defined as an infinite series along two axis, both the axis of idea as well as the axis of meaning. (It's unclear to me what "R" stands for in this context, "reality" perhaps? It doesn't appear to be the same R from Figure 10.)

Figure 12 is the least expository of the diagrams on this page. A complex molecular structure extends vertically through two disk-like membranes, perhaps in an attempt to render visible the "neurophysiological excitation" referenced in Figure 11.

The dramatic Figure 13 depicts an almost mystical model of human consciousness. A large arrow pointing down and to the left represents the stream of everyday life, filled with, one may assume, all sorts of unpredictable sensations and experiences, similar to Figure 11's "perceptual reception of physical symbols." Whereas consciousness itself, depicted as a smaller arrow riding the crest of the larger arrow -- one might even say surfing that crest -- points up and to the right, advancing as a counter-current to the flow of time underneath.*** Above the conjunction of these two arrows sits a series of loops labeled the seven-fold levels of consciousness. Here the illustration almost resembles an electrical coil, with the seven loops appearing to wrap downward around the arrow of consciousness. I imagine Hollier was thinking about the relationship between electrical coils and magnetism. The electrical loops here would function like a solenoid, with the northward pole of the magnetic field aligning with the tip of the arrow of consciousness, somehow pushing one's mind forward. Overall, Figure 13 is not dissimilar to the kinds of spiritual explorations associated with the "new consciousness" movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

The most surprising part comes at the end. Wilden added the following typewritten postscript underneath Hollier's final drawing: "In keeping with the contextual emphasis of these essays, the reader should know that Hollier is black, and that this essay of his was produced independently of anything I had to say on the subject of analog and digital communication" (201).

We know that Wilden was sympathetic to the Black power movement in the 1960s and supportive of Black and minority students at UCSD. System and Structure begins with an epigraph by the Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver, after all, and Wilden discusses Frantz Fanon here and there in the book along with others from the Black radical tradition. Although, to be clear, System and Structure is primarily devoted to white intellectuals and scientists from Europe and North America. We also know that Wilden was involved in the creation of the Third College at UCSD, known today as Thurgood Marshall College, which was built, in part, to expand the curriculum to new disciplines and to better acknowledge and support students involved in social justice movements. (I thank Seb Franklin for this information on the Third College, which comes from a letter written by Wilden to Gregory Bateson.)

Nevertheless the phrasing of Wilden's postscript clashes with today's mores around racial identity. Wilden "outs" Hollier by racializing him as Black. He justifies his actions by saying they are "in keeping with the contextual emphasis of these essays," that is, with cybernetics, structuralism, and psychoanalysis. In other words Wilder considered Hollier's blackness a form of "context" that the reader would require in order to fully understand his drawings and text. (I'm reminded of Sara Ahmed's discussion of racialization in terms of backgrounding certain things while foregrounding other things.) Suffice it to say that Wilden's postscript to Hollier's essay is a complex ideological dance through which race is assigned but also suspended.

A final disclaimer: I am not a media historian. Many of the facts and historical tidbits mentioned here remain sketchy in my mind and are the result of good faith guesses. Please contact me if you have any further information about Hollier (or Wilden) that may help fill out the picture. As I noted at the top, I was never able to accrue enough material for an extended study. I sincerely hope that another scholar will pick up the thread and fill out the story of Vincent Hollier, who without question deserves a place in the history of Digital Studies.

I didn't even mention that Hollier invented laser tag. That's right, laser tag.

+ + +

* Nelson Goodman has a section on "Analogs and Digits" in his 1968 book Languages of Art. And there are discussions concerning the digital and analog in other early sources including the Macy Conferences. In my view, however, Wilden's is by far the most sophisticated of all the early texts in Digital Studies.

** The generous reader should overlook the small number of mistakes in Hollier's essay. The graphs are slightly misdrawn in Figures 1 and 8. And there is a typo in Figure 13.

*** As I learned only after this death, Hollier was an avid surfer in Southern California.