Two Book Talks

A reminder to please join me on Zoom for two book talks in the coming days..

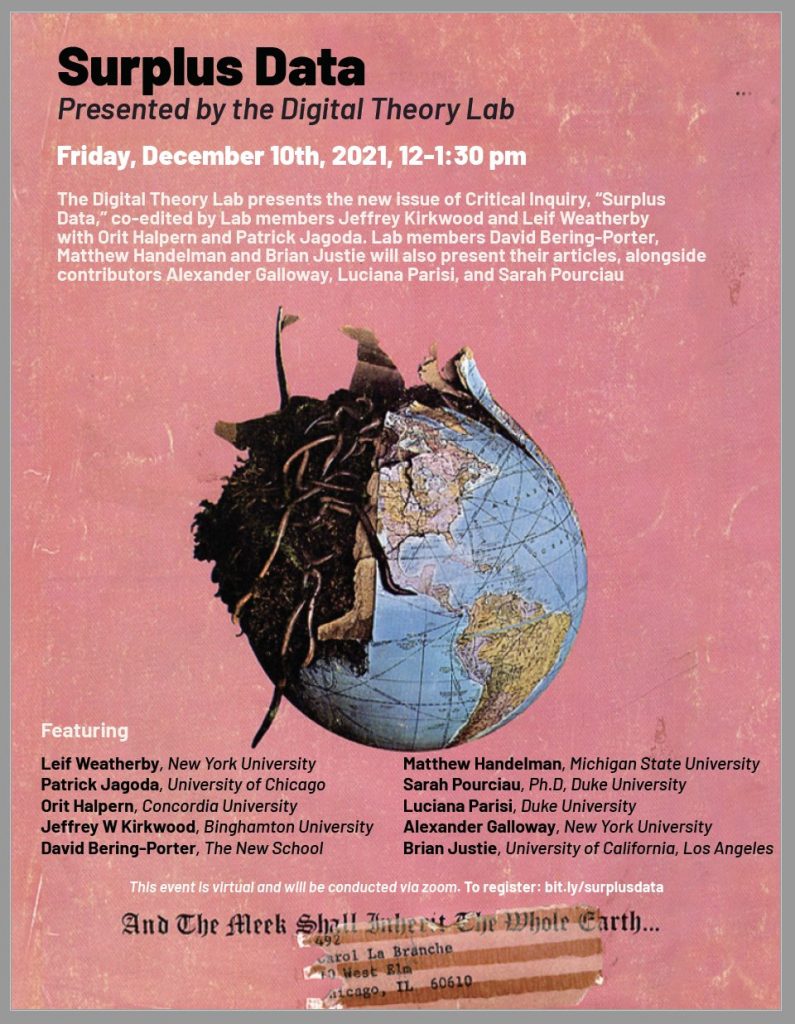

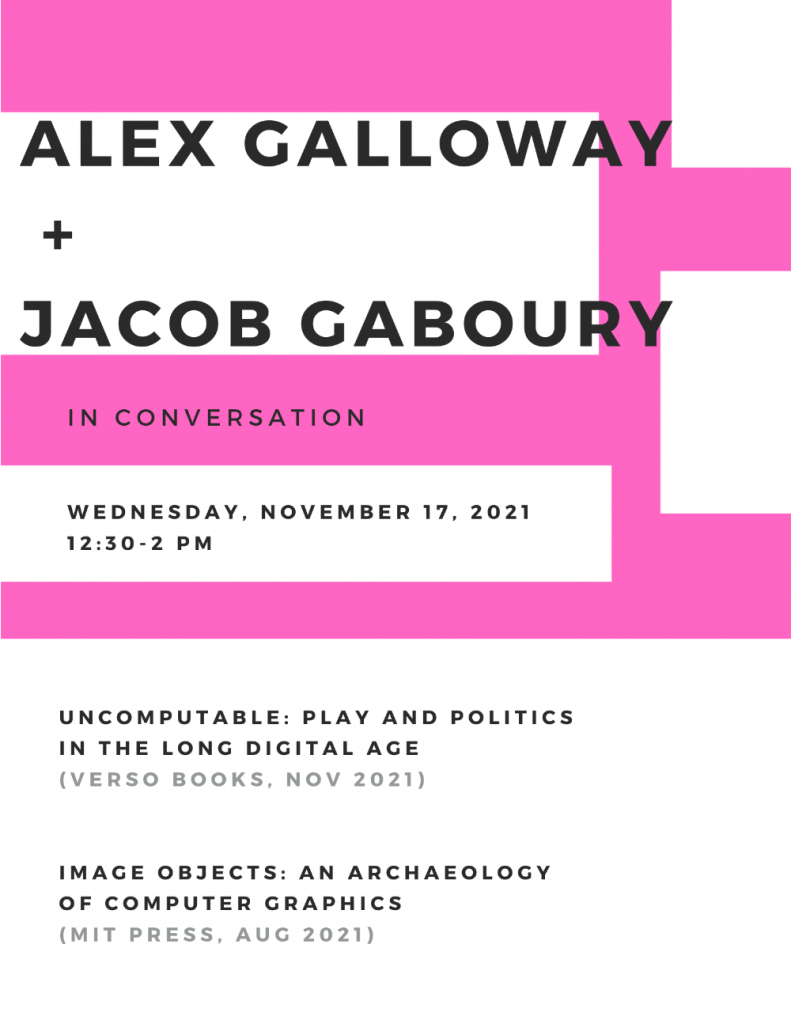

I'll be doing a flip flop with Jacob Gaboury (he talks about my book and I talk about his) this Wednesday, Nov 17 at 12:30pm EST.

And next Tuesday, Nov 23 at 12pm EST Beatrice Fazi, Seb Franklin, and Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan will join to roast me talk about the book.

Looking forward to these conversations.

Premature Optimization Is the Root of All Evil

"Premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming" --Donald Knuth

"Craft is attention to details" --Zach Lieberman

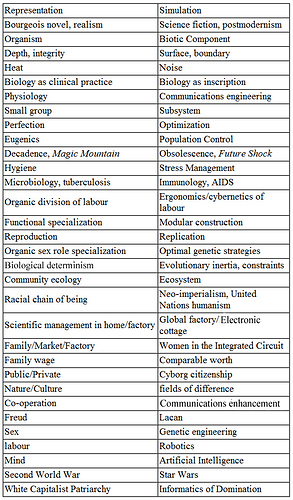

I recently drafted a short text for a friend responding to Donna Haraway's "Informatics of Domination" chart, specifically the pair of terms "Perfection -- Optimization." My assignment was to reflect on these terms, including how Haraway has aligned them to specific historic periods, while also suggesting a third term to add to the pair. (I'll save talking about the third for when the text comes out.)

Perfection and optimization are terms that originate in moral and metaphysical discourse. Perfection refers to something having been fully accomplished, to something in a state of completion. From a Latin root verb meaning "to make," perfection entails a process of production. To perfect something is to intervene positively in its development, to push it in a particular direction, to craft it and finish it and make it shine. Perfection connotes maturity, development, completion.

Book Launch -- With Beatrice Fazi, Seb Franklin, and Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan

Please join me at a book launch event for Uncomputable: Play and Politics in the Long Digital Age, hosted by the Aesthetics and History of Media working group at King’s College London. This event will take place on Zoom, at 12pm EST (5pm GMT) on Tuesday November 23.

We will begin with a short presentation by me, followed by responses from Beatrice Fazi, Seb Franklin, and Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan.

+ + +

Narrating some lesser known episodes from the deep history of digital machines, Alexander Galloway explains the technology that drives the world today, and the fascinating people who brought these machines to life. With an eye to both the computable and the uncomputable, Galloway shows how computation emerges or fails to emerge, how the digital thrives but also atrophies, how networks interconnect while also fray and fall apart. By re-building obsolete technology using today’s software, the past comes to light in new ways, from intricate algebraic patterns woven on a hand loom, to striking artificial-life simulations, to war games and back boxes. A description of the past, this book is also an assessment of all that remains uncomputable as we continue to live in the aftermath of the long digital age.

M. Beatrice Fazi is Reader in Digital Humanities in the School of Media, Arts and Humanities (University of Sussex). Her work explores questions located at the intersection of philosophy, technoscience and culture, and her research interests include media philosophy and theory, digital aesthetics, continental philosophy, computation and artificial intelligence, critical and cultural theory. She is the author of Contingent Computation: Abstraction, Experience, and Indeterminacy in Computational Aesthetics.

Seb Franklin is Senior Lecturer in Contemporary Literature in the Department of English at King’s College London. He is the author of The Digitally Disposed: Racial Capitalism and the Informatics of Value and Control: Digitality as Cultural Logic.

Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan is Senior Lecturer in the History and Theory of Digital Media in the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London. He is a media theorist and historian of science researching how digital technologies shape science, culture, and the environment. His book, From Information Theory to French Theory, is forthcoming from Duke University Press.

Three new essays on the digital and the analog

I'm excited to announce three new essays that will be published in the next few months. I'll link to the texts once they become available.

"Golden Age of Analog," Critical Inquiry 48, no. 2 (Winter 2022)—Why in the digital age have some of our best thinkers turned toward characteristically analog themes?

"The Gender of Math," differences 32, no. 3 (2021)—Math has a gender issue...but how and why? On the problem of essential bias in mathematics, algorithms, and digital media.

"The Origin of Geometry," Grey Room 86 (Winter 2022)—What is a point? Here I address point as unity, puncture, and mark (or in the Greek tradition monas, stigme, and semeion).

Book

Just arrived. Proud parent of a bouncing baby book!

Book Talk w/ Jacob Gaboury - Nov 17

Please join Jacob Gaboury and me for a book talk next month. Webcast here --> https://nyu.zoom.us/meeting/register/tJUrduGopjIvHNTXD75_l1Y3oVgPJX9dPwR3

It will be "criss cross" format -- I'll introduce his new book and he'll do the same for mine.

Ephemera Pt. 3 -- Barricelli's Computable Creatures

Here's some more ephemera from the process of researching and writing Uncomputable. These images pertain to section IV of the book, titled "Computable Creatures," which explores the cellular automata work of Nils Aall Barricelli from the early 1950s. For these chapters I wrote a simple Processing sketch that mimicked Barricelli's original experiments. Here are some of the many failures -- and one or two successes -- in the process of debugging and fine tuning Barricelli's algorithm.

Note these images are meant to be read from top to bottom. They represent a temporal snapshot of evolutionary time. Color fields and textures represent discrete "creatures." According to Barricelli the creatures are alive, they evolve, mutate, and even die.

+ + +

First group.. these are the failures..

Some nice biodiversity through the first few hundred generations, but then disorganized static starts to take over. Barricelli was clear on this point: avoid monoculture but also avoid chaos. Find a balance between the two extremes. Continue reading

Shaky Distinctions: A Dialogue on the Digital and the Analog

Upon reading Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan’s 2019 essay “An Ecology of Operations: Vigilance, Radar, and the Birth of the Computer Screen,” I ended up having an extended email dialogue with the author, which has been condensed and edited here. What struck me most about Geoghegan’s essay was a fundamental question: Are computers a visual medium, like cinema or photography, or are computers better understood in nonvisual terms? While a term like “surveillance” evokes visual metaphors of watching and monitoring within computational capitalism, what if digital media operate more through “capture” and other nonvisual metaphors, as Phil Agre has argued?

Geoghegan and I began by discussing the relation between computation and visuality, but it soon became clear that we had very different positions on the nature of the digital and the analog. The conversation turned toward a slightly different set of questions: What is the digital? What is the analog? Both terms appear elementary at the outset. Yet they turn out to be teeming with technical and philosophical nuance. Conventionally speaking, digital technologies represent the world via discrete units, while analog technologies operate through continuous variation. At the same time, discrete and continuous techniques are some of the oldest in human culture, evident in poetry, music, metaphysics, politics, and many other areas. So do the narrow definitions of digital and analog tech also migrate into domains like aesthetics and philosophy? Would a digital aesthetics follow the principle of discrete units? Would a digital philosophy be discrete as well? And what would that mean in practice?

Digital devices are ubiquitous in contemporary life, yet, as this dialog reveals, some of the most basic questions of the digital age have yet to be answered.

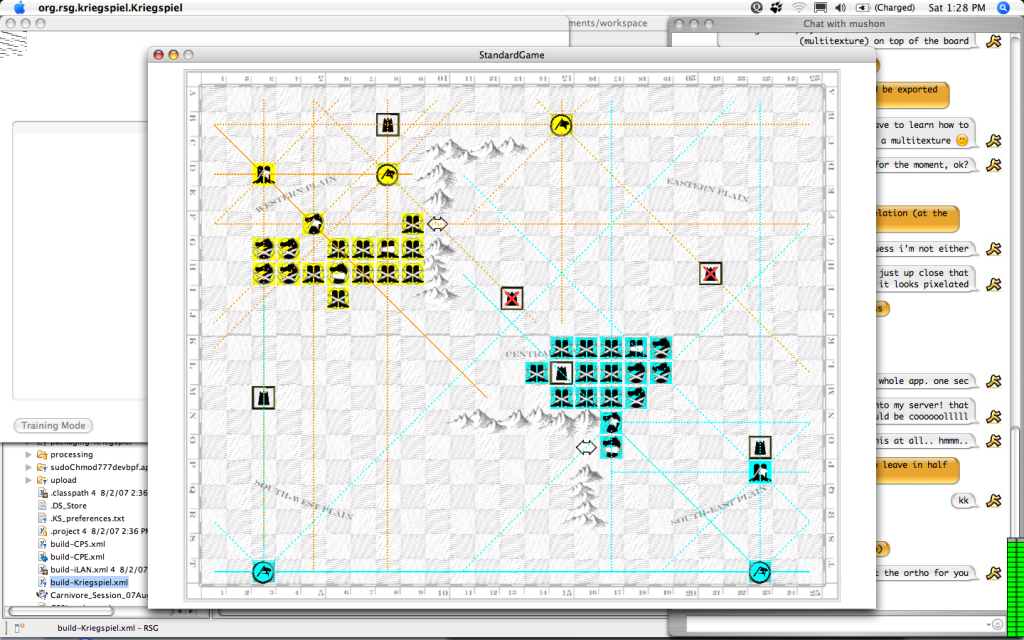

Ephemera Pt. 2 -- Debord & The Game of War

Guy Debord's "Game of War" is a huge part of Uncomputable. He provides the framing narrative in the preface. And section five on "Crystalline War" is largely devoted to Debord and his unexpected turn to game design. While I don't really talk about Kriegspiel in the book -- I wanted to focus on Debord's process, not my process -- I never could have written about Debord's game if I hadn't tried to rebuild it in software. So here's some ephemera collected over the course of designing and coding the Kriegspiel game software.

My deep gratitude to Mushon Zer-Aviv, whose art work appears below.

+ + +

Let's start with some early prototypes..

Developing the prototype. We eventually changed to different art work for the game pieces. Continue reading