From the early 1980s to his death in 1995, the late Deleuze is a period of sustained creativity and refined thinking. I find myself often returning to the late Deleuze. I said before we must forget Deleuze, but the late work is different. We should forget the anti-Oedipus and forget the desiring machines. But Deleuze's intervention in the “Postscript on Control Societies” or his subtle, often touching, exploration of painting in Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation represents a thinker at the height of his powers and with a deep sense of his position in the world.

The crux of the “Postscript” has to do with technology. Here is one of those rare moments in which Deleuze comments on actually existing contemporary technology, specifically computers. Control societies, he writes, “function with a third generation of machines, with information technology and computers” (180). Admittedly Deleuze does not delve too deeply into the specificities of computing. But he does say a few brief words about the pairing that most interests us here, the analog and the digital. Continue reading

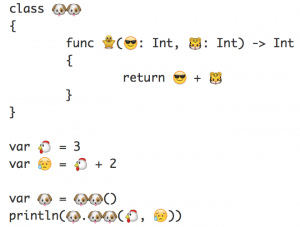

howlers in there, but I'll just correct the obvious mistakes:

howlers in there, but I'll just correct the obvious mistakes: