A not uncommon vignette in higher education: year two of a doctoral program, the student wonders what should I write my dissertation about? The key is to find a suitable research corpus, something that poses an evocative question, something with a rich historical archive, something not too presentist, and of course something that hasn't already been researched to death. I've often thought that someone should write a dissertation about the design patterns. From a media studies perspective, design patterns are a fascinating topic.

What are design patterns? And what makes them so interesting? A design pattern is a set of conventions for how to plan and organize software source code. While the notion of a design pattern is as old as computer programming, the topic was nicely formalized in the 1994 book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. That book defined twenty-three patterns -- although there are others, and not everyone defines the patterns in exactly the same way. A design pattern is like a template, or loose guideline. The design pattern says here is the best general architecture for the problem you want to solve, although the exact coding is still up to you. Some of the design patterns have suggestive names like Flyweight, Memento, Singleton, or Observer.

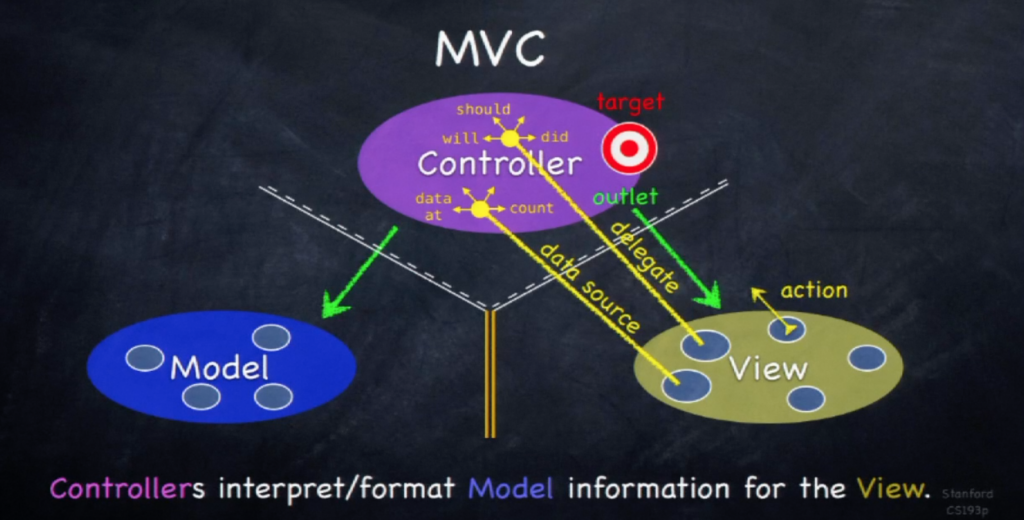

One of the most common patterns in use today is the MVC pattern, short for Model-View-Controller. Although that name is not entirely revealing. The MVC pattern means something like "Data - Display - Algorithm." The MVC pattern is very popular for writing software applications that have a user interface -- which covers a good portion of apps running on smart phones, tablets, and laptops. Most apps on an iPhone for instance follow the MVC pattern to some degree. The essence of the MVC pattern is that your source code should be isolated into three separate groups: the code devoted to the "model" (variables holding the basic data for the app), the code devoted to the "view" (graphics, GUI controls, but also keyboard and mouse input), and the code devoted to the "control" (the set of functions and algorithms that runs the app and mediates between the view and the model).

The rules of good object-based design apply here, meaning that the three elements should, ideally, be firewalled from each other, and connected via interfaces. One popular convention is to have the Control hold strong references to both the Model and the View -- in plain language, it can "talk" directly to them. While the View can talk back to the Control (via a Delegate pattern, more on that in a second), and the Model doesn't communicate back directly, but broadcasts messages using some kind of Observer pattern.

The whole essence of the MVC pattern is found in the philosophy that data shouldn't have anything to do with display. (A staple of western metaphysics, this arrangement goes back to Plato at least.) For instance, a chess game should store the locations of pieces in the Model, but might have any number of Views, a three-dimensional view where the board is rendered in perspective, or a top-down view in two-dimensions; in either view it's still the same model. The data should be oblivious to how it is rendered, and hence none of the data code should contain any display code, and vice versa. The controller sits in the middle, a kind of postmaster general, directing flows between different parts of the app. One benefit of the MVC pattern is that different parts of the application can be swapped out at will; they simply need to fulfill their expected function.

During "shelter in place" I have been coding a lot in Swift for the iOS and macOS platforms. Apple tends to favor the Delegate pattern, and while the pattern originally mystified me, I've grown to like it. The Delegate pattern is frequently used with object interfaces (what are confusingly called "protocols" in Swift). The gist of the Delegate pattern is that a class externalizes or "delegates" some part of what it needs to another class which it communicates with via an interface. The *other* class will need to adopt the interface, and hence fulfill its role as delegate. The Delegate pattern works well in primary/secondary relationships. For instance a primary object might instantiate a secondary object -- just as the Controller might instantiate a View -- yet the secondary object might still need things in reverse from the primary object. The primary object designates itself as delegate -- what do you need? I can provide you with x, y, z -- and the secondary object makes its requests as needed. For instance a GUI toggle button might want to know the default value (pressed on, pressed off) from saved user preferences. The button won't seek the preferences itself, but will delegate this request to the control, which will respond accordingly. The MVC pattern and the Delegate pattern thus work together. The Controller is the delegate for the View, at least that's one way to do it. The key, though, is that one of the two must be primary; a sloppy programmer (read: me last week) might create strong references between the Controller and the View, but this is a recipe for disaster. The delegate should hold a strong reference; the delegator a weak reference. (I've learned a lot about memory leaks and strong reference cycles over the last few days; learned the hard way!)

There are a couple dozen other design patterns, each with a specific structure and ideal use case. I'll admit I have a weakness for the Singleton pattern. (A portion of you are now laughing at me.) Under normal conditions classes can and will instantiate any number of objects. Yet the Singleton pattern ensures that there will only ever be *one* instance object for that class. For this reason, the Singleton pattern is sometimes denigrated as bad style because it essentially undoes the objectness that makes object-oriented software useful. The Singleton pattern is a way to take the OO out of OO. (A Singleton pattern for philosophy you ask? Now why didn't I think of that...) And certainly the Singleton pattern shouldn't be overused. Yet there are many cases when the Singleton pattern makes sense, when you only ever want one object. For instance, if your app is communicating with a server, you might only want a single `client` object to manage the session. Singletons are dumb and easy. There's only one, and it's globally available. No matter where you are in your code, you can always access the static reference of a Singleton object.

From the perspective of digital studies, the design patterns are interesting for a number of reasons. They are a key part of our industrial history, to be sure. Anyone studying software and computation will eventually need to look beyond the user's experience and ponder the ramifications of how software is organized. I've written before about how black boxes, interfaces, and obfuscation all form a cohesive technical device. The importance of this sort of black-box regime is difficult to overstate, and the design patterns would be one entry point for investigating it. Likewise it wouldn't be too hard to do a kind of Foucauldian analysis of design patterns according to the structures of power they embody, servant/client, delegator/delegate, master/slave, and so on.

Yet more generally the design patterns provide a kind of road map for the totality of what's possible in a system so essentially featureless at its core. Software environments are, to be sure, ridiculously artificial and parochial. And within such a bounded purview, software environments provide an amazingly simple set of basic elements: basically just numbers and a few simple ways to manipulate numbers. I can think of few things as featureless as a number. Yet consider the marvelous systems that have been built out of these basic elements. The design patterns are a picture of what can be grown from pure featurelessness. The design patterns are basically an atlas of digitality as a whole.

And it's not just software, but structure and organization more generally. In other words, the design patterns speak to software, to be sure, but also outward to other aspects of life, to social interaction, and even to philosophy. I was joking the other day that the Hobbesians would have their Leviathan pattern, or the Rawlsians their Veil pattern. No reason to omit the Rhizome pattern (Deleuze and Guattari) or the Event pattern (Badiou).

I say "the totality of what's possible" -- of course I mean what has been possible, given the hegemonic mandates of the software industry. The key then would be to characterize the design patterns according to their specific role -- organizational arbiters within the software industry -- while at the same time opening new space to other kinds of patterns: soft patterns, unknown patterns, de-patterned patterns. So many patterns have been left out. And so many other patterns would never be let in. Indeed the success of dominant patterns is predicated on the exclusion of alternate patterns.

Programmers talk about "anti-patterns," by which they mean essentially bad code, whether it be software wrongly crafted by clumsy coders, or apps that otherwise generate pathological user interaction. Spaghetti code or the overuse of Singleton are classic anti-patterns. But what if anti-patterns are not just something to be shunned? In the past I've pondered the anti-computer. What if a whole arena of anti-patterns are waiting to be discovered? Be they pathological, inefficient, plagued by logical regress -- who cares.What if the fabric of daily life is already an anti-pattern, it just hasn't been given that name? I can only imagine how an investigation into anti-patterns might transform the digital landscape. It strikes me as a fine project for the future.