Flatness

- A. Square, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions

In Plato’s Symposium, Aristophanes presents an unusual view of the history of human nature: “the primeval man was round, his back and sides formed a circle; and he had four hands and four feet, one head with two faces, looking opposite ways, set on a round neck and precisely alike; also four ears, two privy members, and the remainder to correspond. He could walk upright as men now do, backwards or forwards as he pleased, and he could also roll over and over at a great pace, turning on his four hands and four feet, eight in all, like tumblers going over and over with their legs in the air; this was when he wanted to run fast.” Zeus, threatened by these children of sun, moon, and earth, splits them in two so they “will be diminished in strength and increased in numbers.” In this story Aristophanes locates the origin of love. He could just as easily locate the origin of inscription media.

This is a study of the "obvious." In this dossier we look at flatness not solely as a tactile characteristic—our walls, floors, and desks reveal that to be thriving—but as a characteristic of information organization. The two dimensional perspective of the torn human, realized in the initial single planar creation of tablet, scroll, and map, defies Zeus by evolving into the multiplanar media of the codex and the globe. This media not only recreates the multi-directional, 360o view but expands it to include innumerable steradians. The speedy tumbling ideal of pre-humanity, lost to direct human physiology due to the wrath of the gods, is regained through random access three-dimensional models. The dominant paradigm of single plane inscription designed the way information was organized, presenting a world view that was flat. Three-dimensional representation of information broadened this perspective to encompass a new complexity. No longer a necessity of mediatic representation, flatness has since become an aesthetic value, while persevering the functionality of three-dimensional representation.

Contents

Bodies of Inscription

The transition to flexible inscription mediums, papyrus and later parchment in Egypt and paper in China broadened the capabilities for inscription. However, these capabilities did not initially broaden the single-planar mindset. Papyrus scrolls varied in length and size, but not in reading method. "The Latin or Greek volume was read from left to right, and when the scroll was held in the hands, the already-read portion was often rolled up in the left hand while the still-to-be read text was unrolled from the right, not unlike the way we handle the pages of a book being read today" and "when a scroll was finished it would have to be rewound to be read again very much as with a modern videotape after it is viewed" (Petroski 25). Scrolling on computer screens is a remediation of this physical movement. Text was written in a series of columns, a format used today in newspapers publications; thus the physical medium also imposed a specific graphical structure of the text. Although the medium of the scroll is analog and continuous, the text of the scroll has digital aspects. Because works could span several scroll the whole is comprised of discreet pieces. Also, the single plane of the scroll is composed of discreet columns, which are approximately uniform. The whole of the text is "split up into little bits" to be more easily digested by the eyes and accessed by the hands (Flusser 62). A "concentration of dots" creates the world of the scroll, but the scroll offered two choices: view the text in piecemeal form in order to use it or view it in its unwieldy entirety. Clay and stone restricted space; scrolls restricted searchability due to the arduous nature of physically wrapping and unwrapping to reveal the contained text.

Whether on parchment and papyrus, scrolls provided a clear recording medium. However, labeling and storage presented difficulties. Meta-text was attached to the ends of scrolls “with tags or tickets, not unlike modern price tags, which were marked to give the necessary information, such as descriptive words, author, and the like" (Petroski 25-26). Easily detached, the loss of these tags was another feature limiting convenient access to the contents. Although storage was easier than with stone, scroll storage was not unfettered. A multi-scroll document would be kept upright in a box or gathered in a shelf cubby, with the limit on the latter that too great a weight from the top would crush the scrolls, which fell to the bottom. Slate or wax writing tablets offered an additional convenient option, particularly for note taking, but each lacked permanence as inscription mediums.

The bound codex, with double-sided sheets, layered in multiple planes, and later the book as we know it, provided greater sophistication as a resource for both organizing and locating previously recorded information. “Where an entire scroll might have to be unrolled to find a passage near the end, the relevant page could be turned to immediately in the codex. Also, writing in a scroll was normally on one side only, whereas the codex lent itself to the use of both sides of the leaf” (Petroski 29). As a result of the increased functionality, already established fields, such as law, became more intricate in their operations. "A new way of binding or of writing things down, a change in the way data are collected, affects the legal framework. It is only in such a diachronic description that the discourse of the law assumes its specific appearances. Only then, by turning into parchment codices, string-tied convolutes, or standardized chrome folders, do files acquires face, form, and format" (Vismann xiii). This ability to search and to tie separate thoughts physically together leads to an increased complexity of the thoughts themselves; the medium shapes the message. In his work Flaubert, Joyce, and Beckett: The Stoic Comedians, Hugh Kenner emphasizes how these authors embraced the physical structure of the book. Before them, "It is the books of reference that think to make use of leaves, sheets, numbered pages, and the fact that all pages of all copies are identical" (Kenner 59). The flimsy metatext of the scroll becomes an integrated part of the object, with titles living on spines and indexes and tables directing a search.

Hypertext adopts the functionality of books and even remediates the terminology of pages, but takes their use beyond the material restrictions of the printed word. The options for the serial and temporal ordering of a text have expanded in ways that no physical page could realistically support. In Ted Nelson's words, a "non-sequential writing, a branching text that allows the reader to make choices…" (Nelson). This web of options operates outside the boundaries of spinal bindings to produce an even greater organizational freedom than even that of the the multi-planar codex.

Maps and Globes

Maps and globes are technologies of representation, conveying the human sensory experience of the outer physical world. While the earliest maps expressed spatial knowledge of a specific place, subsequent versions overlay other relationships. This section concerns two dimensional maps, which display geographic information in graphical detail that still exist today. Maps shaped how early humanity thought about the world due to the limited representative abilities of the planer surface.

While it is difficult to pinpoint when map making truly began, it has roots in many ancient cultures. The British museum has a 5th century BCE Babylonian clay tablet that illustrates the civilization’s belief that the world was round--but not spherical--surrounded by an ocean (Tooley 3). As Crary points out in Techniques of the Observer, both the map and the globe display representations that give the user more information about the world beyond what their own sensory organs provide. The map and the globe are used as tools to extend our own vision and allow people to contemplate the “crucial feature of the world, its extension, so mysteriously unlike the unextended immediacy of their own thoughts yet rendered intelligible to mind by the clarity of these representations, by their magnitudional relations” (Crary 46). Scale is an issue in understanding the world. The curves of the earth's surface appear to be flat because of our vantage point on the massive globe. The flatness of a single-plane medium like a map mirrored early concepts of the world as a whole that were based on this limited visual information. Therefore, the fantasy of flatness as a mediation paradigm was corrected with the development of a global perspective.

The idea that the earth was a flat disc was debated during the Hellenic period, leading the Greeks to make globes in tandem with maps. In addition, renowned polymath Ptolemy drafted maps and developed the concepts of longitude and latitude. Ptolemy, though, placed the prime meridian through the Canary Islands and therefore “greatly overestimated the length of the land surface eastward from this line, and consequently reduced the gap…lying between Europe and Asia” (Tooley 5). While these distortion were mainly based on faulty calculations and assumptions, a flat surface is not capable of accurately capturing the relationships between the landmasses in our spherical world. The distortions are "pops and hisses" of flatness in graphical representations of geography. Globes provide a way to view the world’s geography without distortions. Modern maps are actually projections of the globe onto a flat surface, in contrast to earlier map making. Therefore when flatness is filtered through the lens of the global, our representation of the world is more accurate. When humanity began to think beyond one plane, our understanding of the world was changed.

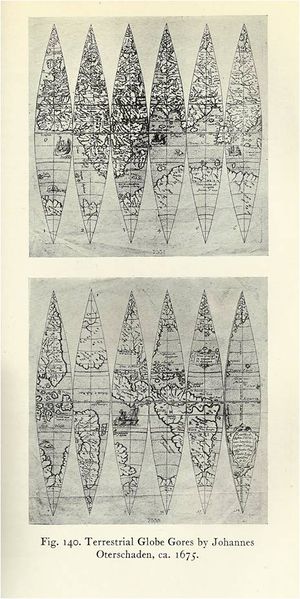

But, while geographers utilize the knowledge that the earth is a sphere to make the most accurate maps, globe gores have been used since at least the 1500s in the production of globes (Stevenson 202). As seen in "Picture 3," gores are maps of the Earth printed in flat, roughly triangular sections. Because of the difficulty of printing or engraving the maps onto a surface that is not flat, these flat maps are attached to a sphere made out of wood, brass or some other medium. Therefore the flat characteristic of a map is remediated in the globe. Some modern globes are still constructed in this way. But, many globes are no longer handmade and are composed of plastic that has dye directly applied to the sphere itself.

Globes are typically tilted on their axis at the same degree the planet is toward the sun, and go along with the “arbitrary” convention that north is upward. Most also can rotate just as the earth does. Ptolemy and other astronomers utilized both terrestrial and celestial globes and the information encoded on them to understand their area of study--the earth’s relation to other heavenly bodies. Due to the physical limits of space, though, only so much information can be housed on a map or a globe. For example, not every city can be labeled on a normal globe because the scale would make the labels unreadable. Additionally, the viewer cannot increase or decrease the magnification of a section of the world, and, as with all physical objects the whole cannot be seen all at once. The material bulk of the globe prevents viewing New York and Perth simultaneously.

These lacks of maps and globes as graphic representation of geographic information have been overcome with the development of digital maps. Contemporary society has found a way to "fix unwritable data flows" (Kittler 14). GPS units, Google Maps, and Google Earth are all examples of modern technologies that display the terrestrial globe on a flat screen with information gathered or dispersed from satellites. This extraterrestrial perspective allows for scalability and overcomes the "pops and hisses" of the material maps and globes. Even though the display is flat, the conceptions behind the technologies take into account the three-dimensional thinking associated with a global perspective.

Deliberate Flatness

Flat media are still in existence; however, now flatness is created as an aesthetic choice. Because flatness has become an explicit choice and not the given paradigm in the creation of media, it is transformed into a different mode of mediation than that previously described. The term ‘deliberate flatness’ should be used to call attention to this aesthetic choice in both media's contents and the media themselves. In either case the use of deliberate flatness is recognized and considered for its effects on the way in which we interact with the medium and with the information it displays.

By calling attention to itself as flat, deliberately flat media are created with an acknowledgment that flatness has become a new, purely aesthetic part of the "obvious" of media. That is, the use of flatness in design is optional, but useful, and through deliberate flatness media produces a very specific message. In this way deliberate flatness is rarely the content, but the form media take. Deliberate flatness has limitations though. It only produces its desired effect with a knowing viewer who understands that flatness is an obvious trait of the medium.

Deliberate flatness does not actually produce a physically flat medium. Many modern media that are made to appear flat have complex content and operations, which produce a juxtaposition within the media's consumer. In this way, deliberate flatness can be thought of as artificial simplicity. The effects of this are to either produce a meta-dialogue about the media or to avoid that kind of discussion as much as possible. Effectively, this choice comes to whether or not media producers want their consumers to be dazzled by their creations or to consider them as creations.

Deliberate Flatness in Art

With all of this revelry in flatness, Greenberg also acknowledges that with any sort of brushstroke on a canvas there is a destruction of the perceived flatness. When a modernist painter makes anything, she produces a “strictly optical third dimension” which “can only be seen into; can be traveled through, literally or figuratively, only with the eye" (Greenberg). This turns painting into a purely visual medium without any kind of escapist ability, once again bringing the art back to being in many ways a commentary on itself.

So here within art, maybe one of the most complex modes of mediation, deliberate flatness is produced, but it is created with a purpose. By using flatness Modernist painters were able to make deep commentary on not just the techniques of art, but on art as a way of seeing the world.

Deliberately Flat Technology

While it could be seen as a purely practical use of flatness, the way in which data is stored for computers has become deliberately flat. While machine-readable data was stored on something flat, these things never seemed flat to us thanks to the surface of the medium itself, such as the grooves of the vinyl record. Flatness was never an issue with records because the text of the record was within the grove, thus making flatness into blankness. And in other forms of machine-readable data, such as magnetic tape, flatness existed, but in a similar fashion to the scroll as a fundamental quality of the medium. Both media paradigms, however, make flatness seem strange to even consider.

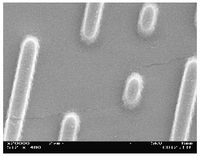

With the introduction of the compact disc flatness suddenly was brought to the front of media. The CD changed the way information was stored and, with this change, turned flatness into a language. Of course, this is not technically true. CDs have very small impressions on their surface, but to the unaided human eye these impressions are impossible to observe (Pohlmann). While the use of machine-written storage media had already created a public comfortable with machines that could “read themselves” as representing technology, the media before CDs were still reading a text which, even if not quite perceivable, was at least connected to a cinematic understanding of media (Gitelman 64). The CD then was hailed as revolutionary because of its deliberate flatness while changing the way we think about memory. To remember something requires a way to see patterns in a place where there is no visible pattern. It is as if all the marks ever made on Freud’s mystic writing pad could only be seen on the bottom surface and never the top. To read the pad one would have to know how to lift the top layer and read carefully the constantly written over indentations. This turns flatness into a barrier that must be lifted before memory (much less the memories content) can be revealed.This deliberate flatness makes things appear to be simple to understand and operate though. So much so is this the case that other forms of media are working toward flatness as a way of manufacturing simplicity. Probably the most recent example of this is the Apple iPad®. While a highly complex piece of technology, it leverages its flatness as a way of making the public more comfortable its operation. Deliberate flatness for the iPad is used in a way to exceed our understanding of how it works in order for it to seem “magical” (iPad). As the iPad’s advertisement even says, “It is hard to see how something so simple, so thin, and so light could possibly be so capable” (iPad). The iPad, like most other consumer electronics, is flat to give the machine’s functions a sense of great depth of wonderment, while simultaneously creating a black box that protects the consumer from being forced to know just how anything works. This black boxing produces a "formal prohibition" against destroying the deliberate flatness of the iPad.

Sources

- Abbott, Edwin Abbott. The Annotated Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Cambridge, MA: Perseus. 2002

- Crary, J. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press. 1990.

- Flusser, Vilém. The Shape of Things: A Philosophy of Design. London: Reaktion Books Ltd. 1999.

- Gitelman, Lisa. Scripts, Grooves, and Writing Machines. Stanford University Press: Stanford. 1999.

- Greenberg, Clement. Modernist Painting. Forum Lectures. Voice of America: Washington D.C. 1960.

- Jean, Georges. Writing: The Story of Alphabets and Scripts. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers: New York. 1992.

- Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. tanford University Press: Stanford. 1999.

- Kenner, Hugh. Flaubert, Joyce, and Beckett: The Stoic Comedians. Beacon Press: Boston. 1962.

- Marks, Philippa J.M. The British Library Guide to Bookbinding: History and Techniques. University of Toronto Press: Toronto. 1998.

- Nelson, Theodor H. Literary Machines 93.1 Mindful Press: Sausalito CA. 1992.

- iPad Video. Apple. Accessed April 10, 2010.

- Petroski, Henry. The Book on the Bookshelf. Alfred A. Knoff: New York. 1999.

- Pohlmann, Ken C. The Compact Disc Handbook. A-R Editions Inc: Middleton. 1992.

- Roberts, Colin H. and Skeat, T.C. The Birth of the Codex. The Oxford University Press: London. 1987.

- Simmonds, Byron. "Divine Art: Torah Scroll". [1] BBC. Accessed April 11, 2010.

- Stevenson, E. L. Terrestrial and Celestial Globes. Yale University Press: New Haven. 1921.

- Tooley, R. V. Maps and Map-Makers. Bonanza Books: New York. 1949.

- Vismann, Cornelia. Files: Laws and Media Technology. Stanford University Press: Stanford. 2008.