Don’t look at part I, put it aside... Or so goes Louis Althusser’s warning to first-time readers of Marx’s Capital. It is important to skip part I of the treatise, Althusser advised, at least on the first couple of reads. Only when the truth of Capital is fully internalized, its scientific intervention into the “new continent” of history, one may “begin to read Part I (Commodities and Money) with infinite caution, knowing that it will always be extremely difficult to understand, even after several readings of the other Parts, without the help of a certain number of deeper explanations.”

Don’t look at part I, put it aside... Or so goes Louis Althusser’s warning to first-time readers of Marx’s Capital. It is important to skip part I of the treatise, Althusser advised, at least on the first couple of reads. Only when the truth of Capital is fully internalized, its scientific intervention into the “new continent” of history, one may “begin to read Part I (Commodities and Money) with infinite caution, knowing that it will always be extremely difficult to understand, even after several readings of the other Parts, without the help of a certain number of deeper explanations.”

After all, Althusser argued, the same political division between social classes was mirrored within the text as an epistemological division. Part I contains something close to philosophical idealism, followed by the scientific materialism of the rest of the book. Althusser’s advice was thus both practical and political: Part I is not only difficult reading for the young and the uninitiated—Althusser admitted that members of the proletariat would have no problem reading the book because their “class instinct” was already attuned to the quotidian experience of capitalist exploitation—it also risks derailing the reader into dangerously Hegelian and philosophical diversions. “This advice is more than advice,” he whispered. It is “an imperative.”

Did he know it? Did Althusser see the colossus issuing forth in the wake of such advice, advice written in March 1969 at such a profound historical conjuncture in France and indeed the world? Was he aware that this would solidify the agenda for the next few decades of Marxian or otherwise progressive philosophy and theory? The colossus of exchange.

By focusing on surplus-value instead of, say, the commodity, by insisting that Capital and Capital alone be the text by which Marx is judged, therefore sidelining the crypto-Hegelian “young Marx” of species-being and alienation, Althusser placed the emphasis squarely on the scientific structures of exchange: the spheres of production and circulation, the factory floor and the marketplace, the passage from small-scale industry to imperialism. Such an emphasis would continue to dominate theory for decades, both in France and through the adoption of French theory in the English-speaking world. Stemming from his reinterpretation in the 1960s and ’70s, Marx would be rethought primarily as a theorist of exchange. Mating Marx with Freud, theorists like Jean-Joseph Goux would begin to speak in terms of “symbolic economies” evident across all spheres of life, whether psychoanalytic, numismatic, or semiotic. Indeed, life would be understood exclusively in terms of relations of exchange.

Even deviations from capitalist exchange, as in the many meditations on “the gift,” or even, in a very different way, Deleuze and Guattari’s writings on desiring machines, would conserve exchange as the ultimate medium of relation. The gift economies of the Haida or Salish potlatch might not be capitalist, but they remain economies nonetheless. Desiring machines might find fuel for their aleatory vectors from beyond the factory walls, but they remain beholden to the swapping of energies, the pathways of flight lines, and the interrelation of forces of intensification and dissipation.

Althusser had merely identified a general paradigm, that systems of relation exist, and that they are prime constituting factors for all the other elements of the world, from objects to societies. As a general philosophical paradigm it would thus forge common currency with other existing schools, chief among them phenomenology, which must assent to a fundamental relation between self and world, or even the tradition of metaphysics in general, which assumes a baseline expressive model from Being to being, from essence to instance, or from God to man. For Marxists, the fundamental relation is always one of antagonism, hierarchy, inequality, or predation.

All of this is contained in what Fredric Jameson has called the second fundamental riddle in Capital, the riddle contained in the equation M—M’ (from money to “money prime” or money with a surplus added). Such is the riddle of exchange: How does money of one value transform into money of a greater value? To answer the question, Marx had to “descend into the hidden abode of production,” revealing the intricacies of the labor process and the working day, in order ultimately to show the origins of surplus value, what Althusser (and indeed Marx himself) considered the “illuminating heart” of Capital.

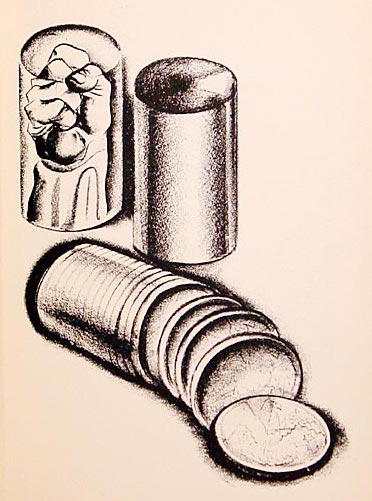

But exchange is still just the second riddle in Marx. Capital is propelled by another riddle, one that finds its voice in the elusive part I, the part that Althusser warned his readers to avoid. “The mystery of an equivalence between two radically different qualitative things”—this is the first riddle, according to Jameson. “How can one object be the equivalent of another one?” In other words, the riddle is the riddle of A = B. The real things constituting A and B themselves, as, for example, twenty yards of linen (as A) and one coat (as B), contribute nothing to the riddle. Rather the mystery derives from the unexplainable, and indeed violent, possibility of inserting an equals sign between different things. The riddle is the riddle of the equation; the violence of capital is the violence of the equality of inequality.

Or as Jameson puts it, “It seems possible to read all of Part One [of Capital] as an immense critique of the equation as such.”

The Mystery of the Fetishistic Character of Commodities Exchange"

(Excerpted from Laruelle: Against the Digital [University of Minnesota Press: 2014], pp. 115-117.)