Figure 1. Caspar David Friedrich, “Woman at a Window,” 1822. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

The Unworkable Interface1

I. Interface as Method

Interfaces are back, or perhaps they never left. The familiar Socratic conceit, from the Phaedrus, of communication as the process of writing directly on the soul of the other has, since the 1980s and ‘90s, returned to center stage in the discourse around culture and media. The catoptrics of the society of the spectacle is now the dioptrics of the society of control. Reflective surfaces have been overthrown by transparent thresholds. The metal-detector arch, or the graphics frustum, or the Unix socket--these are the new emblems of the age.

Windows, doors, airport gates and other thresholds are those transparent devices that achieve more the less they do: for every moment of virtuosic immersion and connectivity, for every moment of volumetric delivery, of inopacity, the threshold becomes one notch more invisible, one notch more inoperable. As technology, the more a dioptric device erases the traces of its own functioning (in actually delivering the thing represented beyond), the more it succeeds in its functional mandate; yet this very achievement undercuts the ultimate goal: the more intuitive a device becomes, the more it risks falling out of media altogether, becoming as naturalized as air or as common as dirt. To succeed, then, is at best self-deception and at worst self-annihilation. One must work hard to cast the glow of unwork. Operability engenders inoperability.

Curiously this is not a chronological, spatial, or even semiotic relation. It is primarily a systemic relation, as Michel Serres rightly observed in his meditation on functional “alongsidedness”:

Systems work because they don’t work. Non-functionality remains essential for functionality. This can be formalized: pretend there are two stations exchanging messages through a channel. If the exchange succeeds--if it is perfect, optimal, immediate--then the relation erases itself. But if the relation remains there, if it exists, it’s because the exchange has failed. It is nothing but mediation. The relation is a non-relation.2

Thus since Plato we have been wrestling with the grand choice: (1) mediation as the process of imminent if not immediate realization of the other (and thus at the same time the self), or (2) as Serres’ dialectal position suggests, mediation as the irreducible disintegration of self and other into contradiction.3 Representation is either clear or complicated, either inherent or extrinsic, either beautiful or deceptive, either already known or imminently interpretable. In short, either Iris or Hermes.

Without wishing to upend this neat and tidy formulation, it is still useful to focus on the contemporary moment to see if something slightly different is going on, or at the very least to “prove” the seemingly already known through close analysis of some actual cultural artifacts.

First though I would like to insinuate a brief prefatory announcement on methodology. To the extent that the present project is allegorical in nature, it might be useful to, as it were, subtend the process of allegorical reading in the age of ludic capitalism with some elaboration as to how or why it might be possible to perform such a reading in the first place. In former times it was generally passable to appeal to some legitimizing methodological foundation--usually Marx or Freud or some combination thereof--in order to prove the efficacy, and indeed the political potency, of one’s critical maneuverings. This is not to suggest that those sources are no longer viable, quite the opposite, since power typically grows with claims of obsolescence; even today Marx’s death drive persists under the pseudonyms of Antonio Negri, Paolo Virno, or McKenzie Wark, just as a generation ago it persisted under Jean-Joseph Goux or Guy Debord. Yet somehow today the unfashionable sheen and indeed perceived illegitimacy of the critical tradition inherited from the middle of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, with Marx and Freud standing as two key figures in this tradition but certainly not encompassing all of it, makes it difficult to rally around the red flag of desire in the same way as before. Today the form of Marxism in common circulation is still the antiseptic one invented a generation ago by Althusser: Marx may be dissected with rubber gloves, the rational kernel of his thought cut out and extruded into some form of scientific discourse of analysis--call it critique or what have you. On the other front, to mention psychoanalysis these days generally earns a smirk if not a condescending giggle, a wholesale transformation from the first half of the twentieth century in which Freudianisms of various shapes and sizes saturated the popular imagination. Realizing this, many have turned elsewhere for methodological inspiration.

Nevertheless Marx and Freud still allow us the ability to do two important things: (1) provide an account for the so-called depth model of interpretation; (2) provide an account for how and why something appears in the form of its opposite. In our times, so distressed on all sides by the arrival of neoliberal economism, these two things together still constitute the core act of critique. So for the moment Marx and Freud remain useful, if not absolutely elemental, despite a certain amount of antiseptic neutering.

But times have changed, have they not? The social and economic conditions today are different from what they were one hundred or one hundred and fifty years ago. Writers from Manuel Castells to Alan Liu to Luc Boltanski have described a new socio-economic landscape, one in which flexibility, play, creativity, and immaterial labor--call it ludic capitalism--have taken over from the old concepts of discipline, hierarchy, bureaucracy, and muscle. In particular, two historical trends stand out as essential in this new play economy. The first is a return to romanticism, from which today's concept of play receives an eternal endowment. Friedrich Schiller’s On the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795) is emblematic in this regard. In it the philosopher uses dialectical logic to arrive at the concept of the play-drive, the object of which is man’s “living form.” This notion of play is one of abundance and creation, of pure unsullied authenticity, of a childlike, tinkering vitality perennially springing forth from the core of that which is most human. More recently one hears this same refrain in Johan Huizinga’s book on play Homo Ludens (which has been cited widely across the political spectrum, from French Situationists to social conservatives), or even in the work of the poststructuralists, often so hostile to other seemingly “uninterrogated” concepts.4

The second element is that of cybernetics, a synthesis across several scientific disciplines (game theory, ecology, systems theory, information theory, behaviorism) that, while in development during and before World War II, seemed to gel rapidly in 1947 or 1948, soon becoming a new dominant. With cybernetics the notion of play adopts a special interest in homeostasis and systemic interaction. The world’s entities are no longer contained and contextless, but are forever operating within ecosystems of interplay and correspondence. This is a notion of play centered on economic flows and balances, multilateral associations between things, a resolution of complex systemic relationships via mutual experimenting, mutual compromise, mutual engagement. Thus, nowadays one “plays around” with a problem in order to find a workable solution. (Recall the dramatic difference in language between this and Descartes’ “On Method” or other key works of modern, positivistic rationality.)

Today’s play is a synthesis of these two influences: romanticism and systems theory. If the emblematic profession for the former is poetry, the latter is design. The one is expressive, consummated in an instant; the other is iterative, extending in all directions. The two became inextricably fused during the second half of the twentieth century, subsumed within the contemporary concept of play. Thus what Guy Debord called the “juridico-geometric” nature of games is not entirely complete.5 He understood the ingredient of systemic interaction well enough, but he understated the romantic ingredient. Today’s play might better be described as a sort of “juridico-geometric sublime.” Witness the Web itself, which exhibits all three elements: the universal laws of protocological exchange, sprawling across complex topologies of aggregation and dissemination, and resulting in the awesome forces of “emergent” vitality. This is what romantico-cybernetic play means. Today’s ludic capitalist is therefore the consummate poet-designer, forever coaxing new value out of raw, systemic interactions (consider the example of Google). And all the rest has changed to follow the same rubric: labor itself is now play, just as play becomes more and more laborious; or consider the model of the market, in which the invisible hand of play intervenes to assess and resolve all contradiction, and is thought to model all phenomena, from energy futures markets, to the “market” of representational democracy, to haggling over pollution credits, to auctions of the electromagnetic spectrum, to all manner of super-charged speculation in the art world. Play is the thing that overcomes systemic contradiction, but always via recourse to that special, ineffable thing that makes us most human. It is, as it were, a melodrama of the rhizome.

Following these types of periodization arguments, some point out that as history changes so too must change the act of reading. Thus, the argument goes, as neoliberal economism leverages the ludic flexibility of networks, so too must the critic resort to new methodologies of scanning, playing, sampling, parsing, and recombining. The critic might then be better off as a sort of remix artist, a disk jockey of the mind.

Maybe so. But while the forces of ludic distraction are many they coalesce around one clarion call: be more like us. To follow such a call and label it nature serves merely to reify what is fundamentally an historical relation. The new ludic economy is in fact a call for violent renovation of the social fabric from top to bottom using the most nefarious techniques available. That today it comes under the name of Google or Monsanto is a mere footnote.

So let me be the first to admit that the present methodology is not particularly rhizomatic or playful in spirit, for the spirit of play and rhizomatic revolution have been deflated in recent years. It is instead that of a material and semiotic “close reading” aspiring not to reenact the historical relation (the new economy), but to identify the relation itself as historical. What I hope this produces is a perspective on what form cultural production and the socio-historical situation take as they are merged together. Or if that is too much jargon: what form art and politics take. If this will pass as an adequate syncretism of Freud and Marx, with a few necessary detours nevertheless back to Deleuze and elsewhere, then so be it.

Yet the ultimate task in this essay is not simply to illustrate the present cocktail of methodological influences necessary to analyze today's ludic interfaces. For that is putting the cart before the horse. The ultimate task is to reveal that this methodological cocktail is itself an interface. Or more precisely, it is to show that the interface itself, as a "control allegory," indicates the way toward a specific methodological stance. The interface asks a question and, in so doing, suggests an answer.

Begin first with the received wisdom on interfaces. Screens of all shapes and sizes tend to come to mind: computer screens, ATM kiosks, phone keypads, and so on. This is what Vilém Flusser called simply a “significant surface,” meaning a two-dimensional plane with meaning embedded in it or delivered through it. There is even a particular vernacular adopted to describe or evaluate such significant surfaces. We say “they are user-friendly,” or “they are not user-friendly.” “They are intuitive” or “they are not intuitive.”

But at the same time it is also quite common to understand interfaces less as a surface but as a doorway or window. This is the language of thresholds and transitions already evoked at the outset. Following this position, an interface is not something that appears before you, but rather is a gateway that opens up and allows passage to some place beyond. Larger twentieth century trends around information science, systems theory, and cybernetics add more to the story. The notion of the interface becomes very important for example in the science of cybernetics, for it is the place where flesh meets metal, or in the case of systems theory the interface is the place where information moves from one entity to another, from one node to another within the system.

The doorway/window/threshold definition is so prevalent today that interfaces are often taken to be synonymous with media themselves. But what would it mean to say that "interface" and "media" are two names for the same thing? The answer is found in the layer model, wherein media are essentially nothing but formal containers housing other pieces of media. This is a claim most clearly elaborated on the opening pages of Marshall McLuhan's Understanding Media. McLuhan liked to articulate this claim in terms of media history: a new medium is invented, and as such its role is as a container for a previous media format. So, film is invented at the tail end of the nineteenth century as a container for photography, music, and various theatrical formats like vaudeville. What is video but a container for film. What is the web but a container for text, image, video clips, and so on. Like the layers of an onion, one format encircles another, and it is media all the way down. This definition is well-established today and it is a very short leap from there to the idea of interface, for the interface becomes the point of transition between different mediatic layers within any nested system. The interface is an “agitation,” or generative friction between different formats. In computer science this happens very literally; an “interface” is the name given to the way in which one glob of code can interact with another. Since any given format finds its identity merely in the fact that it is a container for another format, the concept of interface and medium quickly collapse into one and the same thing.

But is this the whole story of the interface? The parochialism of those who fetishize screen-based media suggests that something else is going on too. If the remediation argument has any purchase at all it would be shortsighted to limit the scope of one’s analysis to a single medium or indeed a single aggregation under the banner of something like “the digital.” The notion of thresholds would warn against it. Thus a classical source, selected for its generic quality, not its specificity, is now appropriate. How does Hesiod begin his song?

The everlasting immortals...

It was they who once taught Hesiod his splendid singing. [...]

They told me to sing the race of the blessed gods everlasting,

but always to put themselves at the beginning and end of my singing.6

A similar convention is found in Homer and in any number of classical poets: "Sing in me Muse, and through me tell the story of..." The poet does not so much originate his own song than serve as conduit for divine expression received from without. The poet is, in this sense, wrapped up by the Muse, or as Socrates puts it in the Phaedrus, possessed. "To put themselves at the beginning and end"--I suggest that this is our first real clue as to what an interface is.

Most media, if not all media, evoke a similar liminal transition moment in which the outside is evoked in order that the inside may take place. In the case of the classical poet, what is the outside? It is the Muse, the divine source, which is first evoked and praised, in order for the outside to possess the inside. Once possessed by the outside the poet sings and the story transpires.

Of course this observation is not limited to the classical context. Prefatory evocations of the form "once upon a time" are common across media formats. The French author François Dagognet describes it thus: “The interface [...] consists essentially of an area of choice. It both separates and mixes the two worlds that meet together there, that run into it. It becomes a fertile nexus.”7 Dagognet presents the expected themes of thresholds, doorways, and windows. But he complicates the story a little bit in admitting that there are complex things that take place inside that threshold; the interface is not simple and transparent, but a “fertile nexus.” He is more Flusser and less McLuhan.8 The interface for Dagognet is a special place with its own autonomy, its own ability to generate new results and consequences. It is a “area of choice” between the Muse and the poet, between the divine and the mortal, between the edge and the center.

But what is an edge and what is a center? Where does the image end and the frame begin? This is something with which artists have played for generations. Digital media are exceptionally good at artifice and often the challenge comes in maintaining the distinction between edge and center, a distinction that threatens to collapse at any point like a house of cards. For example, the difference is entirely artificial between legible ASCII text, on a Web page for example, and ASCII text used in HTML markup on that same page. It is a matter of syntactic techniques of encoding. One imposes a certain linguistic and stylistic construct in order to create these artificial differentiations. Technically speaking, the artificial distinction is the case all the way down: there is no essential difference between data and algorithm, the differentiation is purely artificial. The interface is this state of "being on the boundary." It is that moment where one significant material is understood as distinct from another significant material. In other words an interface is not a thing, an interface is always an effect. It is always a process or a translation. Again Dagognet: a fertile nexus.

To distill these opening observations into something of a slogan one might say that the edges of art always make reference to the medium itself. Admittedly this is a common claim, particularly within discourse around modernism. But it is possible to expand the notion more broadly so that it applies to the act of mediation in general. Homer invokes the Muse, the literal form of poetry, in order to enact and embody that same divine form. But even in the song of the poem itself, Homer turns away from the narrative structure, in an apostrophe, to speak to a character as if he were an object of direct address: “And you, Atrides...,” “and you, Achilles...”

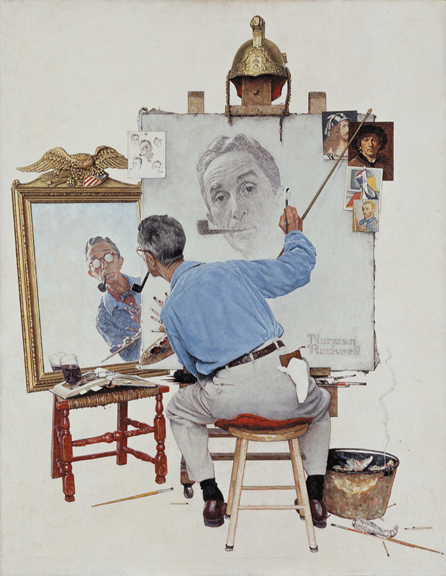

To develop this thread further I turn to the first of two case studies. Norman Rockwell’s “Triple Self-Portrait” (1960) presents a dazzling array of various interfaces. It is, at root, a mediation on the interface itself. The portrait of the artist appears in the image, only redoubled and multiplied a few times over. But the illustration is not a perfect system of representation. There is a circulation of coherence within the image that gestures toward the outside, while ultimately remaining afraid of it. Three portraits immediately appear: (1) the portrait of an artist sitting on a stool, (2) the artist’s reflection in the mirror, and (3) the half-finished picture on the canvas. Yet the image does not terminate there, as additional layers supplement the three obvious ones: (4) a prototypical interface of early sketches on the top left of the canvas, serving as a prehistory of malformed image production; (5) on the top right, an array of self-portraits by European masters that provide the artist some inspiration; and (6) a hefty signature of the (real) artist at center right, craftily embedded inside the image, inside another image.

This complicated circulation of image production produces a number of unusual side effects that must be itemized. First, the artist paints in front of an off-white sweep wall, not unlike the antiseptic, white nowhere land that would later become a staple of science fiction films like THX 1138 or The Matrix. Inside this off-white nowhere land, there appears to be no visible outside--no landscape at all--to locate or orient the artist's coherent circulation of image production. But second, and more important is the dramatic difference in representational and indeed moral and spiritual vitality between the image in the mirror and the picture on the canvas. The image in the mirror is presented as a technical or machinic image, while the picture on the canvas is a subjective, expressive image. In the mirror the artist is bedraggled, dazzled behind two opaque eyeglass lenses, performing the rote tasks of his vocation (and evidently not entirely thrilled about it). On the canvas instead is a perfected, special version of himself. His vision is corrected in the canvas world. His pipe no longer sags but shoots up in a jaunty appeal. Even the lines on the artist’s brow lose their foreboding on canvas, signifying instead the soft wisdom of an elder. Other dissimilarities abound, particularly the twofold growth in size and the lack of color in the canvas image, which while seemingly more perfect is ultimately muted and impoverished. But there is a fourth layer of this interface, the “quadruplicate” supplement to the triple self-portrait: the illustration itself. It is also an interface, this time between us and the magazine cover. This is typically the level of the interface that is most invisible, particularly within the format of middlebrow kitsch of which Rockwell is a master. The fact that this is a self-conscious self-portrait also assists in making that fourth level invisible, because all the viewer’s energies that might have been reserved for tackling those difficult “meta” questions about reflections and layers and reflexive circulation of meaning are exercised to exhaustion before they have the opportunity to interrogate the frame of the illustration itself.

To put it in rather cynical terms, the image is semiotic catharsis, designed to keep the viewer’s eye from straying too far afield, while at the same time avoiding any responsibility of thinking the image as such. The image claims to address the viewer's concerns within the content of the image (within what should be called by its proper name, the diegetic space of the image). But it only raises these concerns so that they may be held in suspension. In a larger sense this is the same semiotic labor that is performed by genre forms in general, as well as kitsch, baroque, and other modes of visceral expression: to implant in the viewer the desires they thought they wanted to begin with, and then to fulfill every craving of that same artificial desire. Artificial desire--can there be any other kind?

But still, what is an edge and what is a center? Have I avoided the question? Is Rockwell evoking the Muse or simply suspending her? Where exactly is the line between the text and the paratext? The best way to answer these questions is not to point to a set of entities in the image, pronouncing proudly that these five or six details are textual, while those seven or eight others are paratextual. Instead, one must always return to the following notion. An interface is not a thing; an interface is a relation effect. One must look at local relationships within the image and ask: How does this specific local relationship create an externalization, an incoherence, an edging, or a framing? (Or in reverse: How does this other specific local relationship within the apparatus succeed in creating a coherence, a centering, a localization?) But what does this mean? Project yourself into Rockwell’s image. There exists a diegetic circuit between the artist, the mirror, and the canvas. The circuit is a circulation of intensity. Nevertheless this does not prohibit the viewer from going outside the circuit. The stress here is that one must always think about the image as a process, rather than as a set of discrete, immutable items. The paratextual (or alternately, the nondiegetic) is in this sense merely the process that goes by the name of outering, of exteriority.

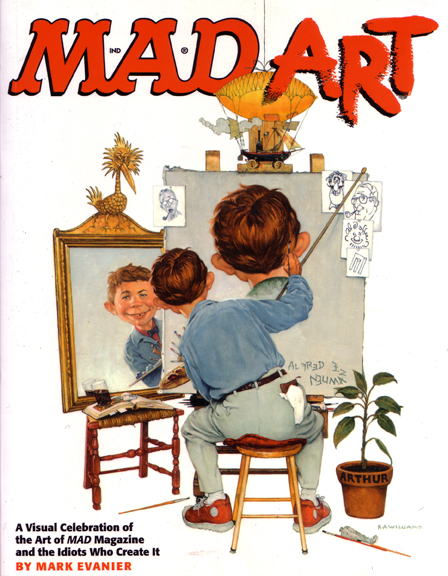

To laugh at the joke, intimated but never consummated by Rockwell’s triple self-portrait, one should turn to the satire produced a few years later by Richard Williams for Mad magazine.9 The humor comes from Mad’s trickster mascot. Being an artist of such great talent, he not only paints a portrait of himself but does so from the viewer’s subjective vantage point. It is a short circuit.

Unlike Rockwell’s avatar, Mad’s mascot has no concern for making himself look better in art, only to make himself appear more clever. There is no anxiety in this image. There is no pipe; there are no glasses. It is in color. It is the same head, only bigger. And of course, it is the view of the back of the head, not the face, front and forward. The mode of address is now the core of the image: Rockwell's eyes were glazed, but the Mad mascot here is quite clearly addressing the viewer. There is an intensity of circulation within Rockwell’s image, whereby each added layer puts a curve into the viewer’s gaze, always gravitating centripetally toward the middle. But in Williams’ Mad satire those circular coherences are replaced by three orthogonal spikes that break the image apart: (1) the face in the mirror looks orthogonally outward at the magazine reader, (2) the seated figure looks orthogonally inward and not at the mirror as the laws of optics would dictate, and likewise (3) the canvas portrait faces orthogonally inward, mimicking the look of the big orthogonal Other, the magazine reader. Every ounce of energy within the image is aimed at its own externalization.

Looking back at the history of art making, one remembers that addressing the viewer is a very special mode of representation that is often saved or segregated or cast off and reserved for special occasions. It appears in debased forms like pornography, or folk forms like the home video, or marginalized political forms like Brechtian theater, or forms of ideological interpellation like the nightly news. Direct address is always treated in a special way. Narrative forms, which are still dominant in many media, almost entirely prohibit it. For example by the 1930s in film direct address is something that cannot be done, at least within the confines of classical Hollywood form. It becomes quite literally a sign of the avant-garde. Yet Mad’s fourth interface, the direct address of the image itself, is included as part of the frame. It is entirely folded into the logic of the image. The gargantuan head on the canvas, in turning away, is in reality turning toward, bringing the edge into the center.

Rockwell and Mad present two ways of thinking about the same problem. In the first is an interface that addresses itself to the theme of the interface; Rockwell’s is an image that addresses image-making in general. But it answers the problem of the interface through the neurosis of repression. In orienting itself toward interfaces, it suggests simultaneously that interfaces don’t exist. It puts the stress on a coherent, closed, abstract aesthetic world. On the other hand the second image solves the problem of the interface through the psychosis of schizophrenia. It returns forever to the original trauma of the interface itself. Reveling in the disorientation of shattered coherence, the second image makes no attempt to hide the interface. Instead, the orthogonal axis of concern, lancing outward from the image, seizes the viewer. In it the logic of the image disassembles into incoherence. So the tension between these two images is that of coherence versus incoherence, of centers creating an autonomous logic versus edges creating a logic of flows, transformations, movement, process, and lines of flight. The edges are firmly evoked in the second image. They are dissolved in the first.

Thus the first is an image that is internally consistent. It is an interface that works. The interface has a logic that may be known and articulated by the interface itself. It works; it works well.

On the other hand, the second is an image that doesn’t work. It is an interface that is unstable. It is, as Maurice Blanchot or Jean-Luc Nancy or Mehdi Belhaj Kacem might say, désoeuvré--nonworking, unproductive, inoperative, unworkable.

III. Intraface

The earlier conventional wisdom on interfaces as doors or windows now reveals its own limitation. One must transgress the threshold, as it were, of the threshold theory of the interface. A window testifies that it imposes no mode of representation on that which passes through it. A doorway says something similar, only it complicates the formula slightly by admitting that that it may closed from time to time, impeding or even blocking the passengers within. The discourse is thus forever trapped in a pointless debate around openness and closedness, around perfect transmission and ideological blockages. This discourse has a very long history, to the Frankfurt School and beyond. And the inverse discourse, from within the twentieth-century avant-garde, is equally stuffy: debates around apparatus critique, the notion that one must make the apparatus visible, that the “author” must be a “producer,” etc. It is a Brechtian mode, a Godardian mode, a Benjaminian mode. The Mad image implicitly participates in this tradition, despite being lowbrow and satirical in tone. In other words, to the extent that the Mad image is foregrounding the apparatus, it is not dissimilar to the sorts of formal techniques seen in the new wave, in modernism, and in other corners of the twentieth-century avant-garde.

The Mad image speaks and says: "I admit that an edge to the image exists--even if in the end it's all a joke--since the edge is visible within the fabric of my own construction." The Rockwell image speaks and says: "Edges and centers may be the subject of art, but they are never anything that will influence the technique of art."

It would be helpful to invent a new term to describe this imaginary dialogue between the workable and the unworkable: the intraface, that is, an interface internal to the interface. The key here is that the interface is within the aesthetic, not a window or doorway separating the space that spans from here to there. Gérard Genette, in his book Thresholds, calls it a “’zone of indecision’ between the inside and outside.”10 It is no longer a question of choice, as it was with Dagognet. It is now a question of nonchoice. The intraface is indecisive for it must always juggle two things (the edge and the center) at the same time.

But what exactly is the zone of indecision? What two things face off in the intraface? It is a type of aesthetic that implicitly brings together the edge and the center. The intraface may thus be defined as an internal interface between the edge and the center, but one that is now entirely subsumed and contained within the image. This is what constitutes the zone of indecision.

| Text | Paratext |

| Diegetic | Nondiegetic |

| Image | Frame |

| Studium | Punctum |

| Aristotle | Brecht |

| Rockwell | Mad |

| Hitchcock | Godard |

| Transparency | Foregrounding |

| Dromenon | Algorithm |

| Realism | Function |

| Window | Mirror |

| 3D model | Heads-up-display |

| Half-Life | World of Warcraft |

| Representation | Metrics |

| Narcissus | Echo |

Now things get slightly more complicated, for consider the following query: Where does political art happen? In many cases--and I refer now to the historically specific mode of political art making that comes out of modernism--the right column (Figure 5) is the place where politicized or avant-garde culture takes place. Consider for example the classic debate between Aristotle and Augusto Boal: Aristotle, in his text on poetics, describes a cohesive representational mode oriented around principles of fear, pity, psychological reversal, and emotional catharsis, while Boal addresses himself to breaking down existing conventions within the expressive mode in order that mankind's political instinct might awaken. The edge of the work is thus an arrow pointing to the outside, that is, pointing to the actually existing social and historical reality in which the work sits. Genette's "indecision" is, in this light, a codeword for something else: historical materialism. The edges of the work are the politics of the work.

But to understand the true meaning of these two columns (Figure 5) today we must consider an example from contemporary play culture, World of Warcraft. What does one notice immediately about the image (Figure 6)? First, where is the diegetic space? It is the cave backdrop, the deep volumetric mode of representation that comes directly out of Renaissance perspective techniques in painting. Alternately, where is the nondiegetic space? It is the thin, two-dimensional overlay containing icons, text, progress bars, and numbers. It deploys an entirely different mode of signification, reliant more on letter and number, iconographic images rather than realistic representational images.

The interface is awash in information. Even someone unfamiliar with the game will notice that the nondiegetic portion of the interface is as important if not more so than the diegetic portion. Gauges and dials have superseded lenses and windows. Writing is once again on par with image. It represents a sea change in the composition of media. In essence, the same process is taking place in World of Warcraft that took place in the Mad magazine cover. The diegetic space of the image is demoted in value and ultimately determined by a very complex nondiegetic mode of signification. So World of Warcraft is another way to think about the tension inside the medium. It is no longer a question of a "window" interface between this side of the screen and that side (for which of course it must also perform double duty), but an intraface between the heads-up-display, the text and icons in the foreground, and the 3D, volumetric, diegetic space of the game itself. On the one side, writing. On the other, image.

What else flows from this? The existence of the internal interface within the medium is important because it indicates the implicit presence of the outside within the inside. And, again to be unambiguous, "outside" means something quite specific: the social. Each of the terms previously held in opposition--nondiegetic/diegetic, paratext/text, the alienation effects of Brecht/emotional catharsis of Aristotle--each of these essentially refers to the tension between a progressive aesthetic movement (again, largely associated with but not limited to the twentieth century) and a more conventional one.

Now the analysis of World of Warcraft can reach its full potential. For the question is never simply a formal claim, that this or that formal detail (text, icon, the heads-up-display) exists and may or may not be significant. No, the issue is a much greater one. If the nondiegetic takes center stage, we can be sure that the "outside," or the social, has been woven more intimately into the very fabric of the aesthetic than in previous times. In short, World of Warcraft is Brechtian, if not in its actually existing political values, than at least through the values spoken at the level of mediatic form. (The hemming and hawing over what this actually means for progressive movements today is a valid question, one that I leave for another essay and another time.) In other words, games like World of Warcraft allow us to perform a very specific type of social analysis, because they are telling us a story about contemporary life. Of course it is common for popular media formats to tell the story of their own times, yet the level of unvarnished testimony available in a game like World of Warcraft is stunning. It is not an avant-garde image, but nevertheless it firmly delivers an avant-garde lesson in politics. At root, the game is not simply a fantasy landscape of dragons and epic weapons, but a factory floor, an information-age sweat shop, custom tailored in every detail for cooperative ludic labor.

By now it should be clear why the door or window theory of the interface is inadequate. The door-window model, handed down from McLuhan, can only ever reveal one thing, that the interface is a palimpsest. It can only ever reveal that the interface is a reprocessing of something that came before. A palimpsest the interface may be, yet it is still more useful to take the ultimate step, to suggest that the layers of the palimpsest themselves are "data" that can be interpreted. To this degree, it is more useful to think of the intraface using the principle of parallel aesthetic events that themselves tell the viewer something about the medium and about contemporary life. A simpler word is "allegory". And on this note it is now appropriate to revisit the "grand choice" mentioned in the opening section on methodology: that representation is either beautiful or deceptive, either intuitive or interpretable. There is a third way: not Iris or Hermes, but the "kindly ones," the Eumenides. For representation, as in Aeschylus' play, is an incontinent body, a frenzy of agitation issuing forth from the social body (the chorus). An elemental methodological relation thus exists between my three central themes: (1) the structure of allegory today, (2) the intraface, and (3) the dialectic between culture and history.

IV. Regimes of Signification

We are now able to return to Norman Rockwell and Mad magazine and, extrapolating from these two modes, make an initial claim about how certain types of ludic texts deal with the interface. The alert observer might argue: "But doesn't the Rockwell image confess its own intimate knowledge of looking and mirroring, of frames and centers, just as astutely as the Mad image, only minus the juvenile one-liner? If so, wouldn't this make for a more sophisticated image? Why denigrate the image for being well made?" And this is true. The Rockwell image is indeed well crafted and exhibits a highly sophisticated understanding of how interfaces work. My claim is less a normative evaluation elevating one mode over the other, and more an observation about how flows of signification organize a certain knowledge of the world and a commitment to it.

I will therefore offer a formula of belief and enactment: Rockwell believes in the interface but doesn't enact it, while Mad enacts the interface, but doesn't believe in it.

The first believes in the interface because it attempts to put the viewer, as a subject, into an imaginative space where interfaces propagate and transpire in full view and without anxiety. But at the same time, as media, as an illustration with its own borders, it does not enact the logic of the interface, for it makes it invisible. Hence it believes in it but doesn't enact it.

By contrast, the second voyages to a weird beyond filled with agitation and indecision, and in arriving there turns the whole hoary system into a silly joke. Hence it enacts it but doesn't believe in it. If the first is a de-objectification of the interface, the second is an objectification of it. The first aims to remove all material traces of the medium, propping up the wild notion that the necessary trauma of all thresholds might be sublimated into mere "content," while the second objectifies the trauma itself into a "process-object" in which the upheaval of social forms are maintained in their feral state, but only within the safe confines of comic disbelief.

We are now in a position to make more general observations about the aforementioned ideas of coherence and incoherence. First, to revisit the terminology: coherence and incoherence compose a sort of continuum, which one might contextualize within the twin domains of the aesthetic and the political. These are as follows:

1) A "coherent aesthetic" is one that works. The gravity of the aesthetic tends toward the center of the work of art. It is a process of centering, of gradual coalescing around a specific being. Examples of this may be found broadly across many media. Barthes' concept of the studium is its basic technique.

2) An "incoherent aesthetic" is one that doesn't work. Here gravity is not a unifying force but a force of degradation, tending to unravel neat masses into their unkempt, incontinent elements. "Incoherent" must not be understood with any normatively negative connotation: the point is not that the aesthetic is somehow unwatchable, or unrepresentable. Coherence and incoherence refer instead to the capacity of forces within the object, and whether they tend to coalesce or disseminate. Thus the punctum, not the studium, is the correct heuristic for mode number 2.

3) A "coherent politics" refers to the tendency to organize around a central formation. This brand of politics produces stable institutions, ones that involve centers of operation, known fields and capacities for regulating the flow of bodies and languages. This has been called a process of "state" formation, or a "territorialization." Coherent politics include highly precise languages for the articulation of social beings. Evidence of their existence may be seen across a variety of actually existing political systems including fascism and national socialism, but also liberal democracy.

4) An "incoherent politics," rather, is one that tends to dissolve existing institutional bonds. It does not gravitate toward a center, nor does it aspire to bring together existing formations into movements or coalitions. It comes under the name of "deterritorialization," of the event, of what some authors optimistically term "radical democracy." The principle here is not that of repeating past performance, of gradually resisting capitalism, or what have you, as in the example of Marx's mole. Instead one must follow a break with the present, not simply by realizing one's desires, but by renovating the very meaning of desire itself.

(Let me repeat that coherent and incoherent are non-normative terms, they must be understood more as "fixed" or "not fixed" rather than "good" or "bad," or "desirable" or "undesirable." I have already hinted at the analogous terms used by Deleuze, "territorialization" and "deterritorialization," but different authors use different terminology. For example in Heidegger the closest cognates are "falling" [verfallen] and "thrownness" [Geworfenheit].)

With these four thus arrayed, one may pair them up in various combinations to arrive at a number of different regimes of signification. First, the pairing of a coherent aesthetic with a coherent politics is what is typically known as ideology--the more sympathetic term is "myth," the less sympathetic is "propaganda." Thus in the ideological regime, a certain homology is achieved between the fixity of the aesthetic and the fixity of the political desire contained therein. (This is not to say that for any ideological formation there exists a specific, natural association between the aesthetic and the political, but simply that there is a similarity by virtue of them both being coherent.) Hence all forms of ideological and propagandistic cultural forms, from melodrama to Michael Moore, Matthew Arnold but also Marx, would be included in this regime. Given the references evoked earlier, it would be appropriate to associate Rockwell with this regime also, in that his image displays an aesthetic of coherence (the intense craft of illustration, the artist as genius, the swirling complexity of the creative process), and a politics of coherence (mom-and-apple-pie and only mom-and-apple-pie).

However if the terms are altered slightly a second pairing becomes visible. Connecting an aesthetic of incoherence to a politics of coherence, one arrives at the ethical regime of signification.11 Here there is always a "fixed" political aspiration that comes into being through the application of various self-revealing or self-annihilating techniques within the aesthetic apparatus. For example, in the typical story of progressive twentieth-century culture, the one told in Alain Badiou's The Century for example, the ethical regime revolves around various flavors of modernist-inspired leftist progressivism. Thus, in Brecht there is an aesthetic of incoherence (alienation effect, foregrounding the apparatus), mated with a politics of coherence (Marx and only Marx). Or again, to evoke the central reference from above, the Mad image offers an aesthetic of incoherence (break the fourth wall, embrace optical illusion), combined with a politics of coherence (lowbrow and only lowbrow). And of course many more names could be piled on: Godard in film (tear film apart to shore up Marxist-Leninism); Fugazi in punk (tear sound apart in the service of the D.I.Y. lifestyle); and so on. However, it should be pointed out that modernist-inspired leftist progressivism is not the end of the story for the ethical regime. I intimated already that I wish to classify World of Warcraft here in calling the game Brechtian. But why? I have given all the reasons already: the game displays an aesthetic of incoherence in that it foregrounds the apparatus (statistical data, machinic functions, respawn loops, object interfaces, multithreading, etc.), while all the time promoting a particularly coherent politics (protocological organization, networked integration, alienation from the traditional social order, new informatic labor practices, computer-mediated group interaction, neoliberal markets, game theory, etc.). So, World of Warcraft is an "ethical" game simply by virtue of the way in which it opens up the aesthetic on the one hand while closing down politics on the other. Again, I am using a general (not a moral) definition of the term term ethical, as a set of broad principles for practice within some normative framework. That World of Warcraft has more to do with the information economy and Godard's La Chinoise has more to do with Maoism does not diminish either in its role within the ethical regime.

A third mode now appears, which may be labeled poetic in that it combines an aesthetic of coherence with a politics of incoherence. This regime is seen often in certain brands of modernism, particularly the highly formal, inward looking wing known as "art for art's sake," but also more generally in all manner of fine art. It is labeled "poetic" simply because it aligns itself with poesis, or meaning making in a general sense. The stakes are not those of metaphysics, in which any image is measured against its original, but rather the semi-autonomous "physics" of art, that is, the tricks and techniques that contribute to success or failure within mimetic representation as such. Aristotle was the first to document these tricks and techniques, in his Ars Poetica, and the general personality of the poetic regime as a whole has changed little since. In this regime lie the great geniuses of their craft (for this is the regime within which the concept of "genius" finds its natural home): Hitchcock or Wilder, Deleuze or Heidegger, much of modernism, all of minimalism, and so on. But you counter: "Certainly the work of Heidegger or Deleuze was political. Why classify them here?" The answer lies in the specific nature of politics in the two thinkers and the way in which the art of philosophy is elevated over other concerns. My claim is not that these various figures are not political, but simply that their politics is incoherent. Eyal Weizman has written of the way in which the Israeli Defense Forces have deployed the teachings of Deleuze and Guattari in the field of battle. This speaks not to a corruption of the thought of Deleuze and Guattari, but to the very receptivity of the work to a variety of political implementations (i.e. its "incoherence"). To take Deleuze and Guattari to Gaza is not to blaspheme them, but to deploy them. Hardt and Negri and others have shown also how the rhizome has been adopted as a structuring diagram for systems of hegemonic power. Again this is not to malign Deleuze and Guattari, simply to point out that their work is politically "open source." The very inability to fix a specific political content of these thinkers is evidence that it is fundamentally poetic (and not ethical). In other words the "poetic" regime is always receptive to diverse political adaptations, for it leaves the political question open. This is perhaps another way to approach the concept of a "poetic ontology," the label Badiou gives to both Deleuze and Heidegger. While for his own part, Badiou's thought is no less poetic, but he ultimately departs from the "poetic" regime thanks to an intricate--and militantly specific--political theory.

The final mode is the most elusive of the four, because it has never achieved any sort of bona fide existence in modern culture, neither in the dominant position nor in the various "tolerated" subaltern positions. This is the dirty regime wherein aesthetic incoherence combines with political incoherence. We shall call it simply truth, although other terms might also suffice (nihilism, radical alterity, the inhuman). The truth regime always remains on the sidelines. It appears not through a "return of the repressed," for it is never merely the dominant's repressed other. Instead, it might best be understood as "the repressed of the repressed," or using terminology from another time and another place, "the negation of the negation." May we associate certain names with this mode, with an incoherence in both aesthetics and politics? May we associate the names of Nietzsche? Of Bataille? Of Derrida? The way forward is not so certain. But it is perhaps better left that way for the time being.

So in summary, these are the four regimes of signification:

(1) Ideological: an aesthetic of coherence, a politics of coherence;

(2) Ethical: an aesthetic of incoherence, a politics of coherence;

(3) Poetic: an aesthetic of coherence, a politics of incoherence;

(4) Truth: an aesthetic of incoherence, a politics of incoherence.

Some commentary on this system is in order before exiting. First, the entire classification system seems to say something about the relationship between art and justice. In the first regime, art and justice are coterminous. One need only to internalize the one to arrive at the other. In the second, the process is slightly different: one must destroy art in the service of justice. In the third it is inverted: one must banish the category of justice entirely to witness the apotheosis of art. And finally, in the fourth, redemption comes in the equal destruction of all existing standards of art and all received models of justice.

Second, after closer examination of these four regimes, it is clear that a hierarchy exists, if not for all time then at least for the specific cultural and historical formation in which we live. That is to say: the first mode is dominant (albeit often maligned), the second is privileged, the third is tolerated, and the final is relatively sidelined. I have thus presented them here in order of priority.

But the hierarchy has little value unless it can be historicized. Thus an additional claim is helpful, reiterated from the above section on World of Warcraft: if anything can be said about the changing uses of these regimes in the age of ludic economies it would be that we are witnessing today a general shift in primacy from 1 to 2, that is to say, from the "ideological" regime to the "ethical" regime. Ideology is in recession today; there is a decline in ideological efficiency. Ideology, which was traditionally defined as an "imaginary relationship to real conditions" (Althusser), has in some senses succeeded too well and, as it were, put itself out of a job. Instead we have simulation, which must be understood as something like an "imaginary relationship to ideological conditions." In short ideology gets modeled in software. So in the very perfection of the ideological regime, in the form of its pure digital simulation, comes the death of the ideological regime, as simulation is "crowned winner" as the absolute horizon of the ideological world. The computer is the ultimate ethical machine. It has no actual relation with ideology in any proper sense of the term, only a virtual relation.

I stress, however, in no uncertain terms that this does not mean that today's climate is any more or less "ethical" (in the sense of good deed doing) or more or less politicized than the past. Remember that the ethical mode (#2) is labeled "ethical" because it adopts various normative techniques wherein given aesthetic dominants are shattered (via foregrounding the apparatus, alienation effects, and so on) in the service of a specific desired ethos.

Finally, given that it is common to bracket both the ideological form (#1) and the truth form (#4), the one banished from respectable discourse out of scorn and the other out of fear, the system may be greatly simplified into just two regimes (#2 and #3), revealing a sort of primordial axiom: the more coherent a work is aesthetically, the more incoherent it tends to be politically. And the reverse is also true: the more incoherent a work is aesthetically, the more coherent it tends to be politically. The primordial axiom (of course it is no such thing, merely a set of tendencies arising from an analysis of actually existing cultural production) thus posits two typical cases, the ethical and the poetic. In simple language, the first is what we call politically significant art; the second is what we call fine art. The first is Godard, the second is Hitchcock. Or if you like, the first is World of Warcraft and the second is Half-Life. The first enacts the mediatic condition but doesn't believe in it; the second believes in the mediatic condition but doesn't enact it.

In the end we might return to our mantra, that the interface is a medium that does not mediate. It is unworkable. The difficulty however lies not in this dilemma, but in the fact that the interface never admits it. It describes itself as a door or a window or some other sort of threshold across which we must simply step to receive the bounty beyond. But a thing and its opposite are never joined by the interface in such a neat and tidy manner. This is not to say that "incoherence" wins out in the end, invalidating the other modes. Simply that there will be an intraface within the object between the aesthetic form of the piece and the larger historical material context in which it is situated. If an "interface" may be found anywhere, it is there. What we call "writing," or "image," or "object," is merely the attempt to resolve this unworkability.

1 This essay was first developed on the invitation of Eric de Bruyn as a seminar on “the interface” at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands on October 24, 2007.

2 Michel Serres, Le Parasite (Paris: Éditions Grasset et Fasquelle, 1980), 107. For the theme of “windows” one should also cite the efforts of the software industry in devising graphical user interfaces. The myth is branded by Microsoft, but it is promulgated across all personal computer platforms, “progressive” (Linux) or less so (Macintosh), as well as all manner of smaller and more flexible devices. A number of books also address the issue, including Jay David Bolter and Diane Gromala, Windows and Mirrors: Interaction Design, Digital Art, and the Myth of Transparency (Cambridge: MIT, 2003), and Anne Friedberg, The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft (Cambridge: MIT, 2006).

3 John Durham Peters puts this quite eloquently in his book Speaking Into the Air (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). For Peters the question is between telepathy and solipsism, with his proposed third, synthetic option being some form of less cynical version of Serres: mediation as a process of perpetual, conscious negotiation between self and other.

4 Jonah Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1950).

5 Guy Debord, Correspondance, volume V: janvier 1973 - décembre 1978 (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2005), 466.

6 Hesiod, Theogony, Richard Lattimore, trans. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959), 124.

7 François Dagognet, Faces, Surfaces, Interfaces (Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1982), 49.

8 Admittedly McLuhan is sharper than my snapshot will allow. Describing the methodology of Harold Innis, he evokes interface as a type of friction between media, a force of generative irritation rather than a simple device for framing one's point of view: "[Innis] changed his procedure from working with a 'point of view' to that of the generating of insights by the method of 'interface,' as it is named in chemistry. 'Interface' refers to the interaction of substances in a kind of mutual irritation." See Marshall McLuhan, "Media and Cultural Change," Essential McLuhan (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 89.

9 I first learned of this delightful satire by attending a lecture by the artist Art Spiegelman at New York University on October 6, 2007.

10 Gérard Genette, Seuils (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1987), 8.

11 I take some terminological inspiration from Jacques Rancière's amazing little book Le partage du sensible: esthétique et politique (Paris: La Fabrique, 2000), published in English as The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (New York: Continuum, 2004). Any similarity to his ethical-poetic-aesthetic triangle is superficial at best, particularly in that his "ethical" is closely aligned with a Platonic moral philosophy, while mine refers primarily to an ethic as an active, politicized practice. Yet overlap exists, as between both uses of the term "poetic," as well as a rapport between his "aesthetic" and my "truth" to the extent that both terms refer to an autonomous space in which the aesthetic begins to refer back to itself and embark on its own absolute journey