Difference between revisions of "Dymaxion House"

(→The Failure of A House is a Labor of Love) |

|||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

Pitter-Patter On the Roof Published: May 31, 1992 | Pitter-Patter On the Roof Published: May 31, 1992 | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | To the Editor:<br /> | ||

| − | + | In reading Witold Rybczynski's essay "A Little House on the Prairie Goes to a Museum" [ April 19 ] , I was reminded of the time in 1944 when I participated in a conference with Buckminster Fuller regarding his Dymaxion House. I attended at the request of my boss. He told me he would like to have an engineer accompany him. (I am an aeronautical engineer.) He wanted me as window dressing. Since I might feel uncomfortable if I said nothing, he advised, "You can say anything you feel like." We drove to the New Jersey Meadowlands, where we discussed the possibility of my boss financing a 500-house development. It was wonderful to hear Fuller's description of the technical achievements in his house, and the idea of a central compression column and thin curtain walls sounded extremely efficient. I realized that the three-hour conference was almost over and I had not made a single comment, so I asked: "Mr. Fuller, Grumman Aircraft gave me an employee's discount on an aluminum canoe. I like the canoe, but it isn't good for fishing because of the noise the water makes against the hollow aluminum. Would the noise on the roof be bothersome?" He laughed and said, "Well, I hadn't thought of that." On the way back to New York, I asked my boss if he was going to buy the houses, and he told me he was not. I said, "Why not? They seem so exciting." He told me it was because of the question I had asked and explained: "It wasn't your question; it was his answer. If he hadn't thought of that, I wondered how many other things he hadn't thought of."<br /> - LEONARD M. GREENE White Plains, N. Y. </blockquote> | |

While Fuller certainly saw and understood many problems of the future of housing, such as energy and water consumption, inefficiencies of space and raw materials, and excessive upkeep requirements, he failed to understand the purpose of a house as a home. The cold, specific and deliberate nature of the Dymaxion House left little input for the dwellers, who were more fulfilling the requirement of inhabitant rather than homeowner, seen as simply another machine expected to act in a logical manner within the environment. Having such a well thought out dwelling was a drastic shift from the organic standard of homemaking, failing to fully realize that the purpose of home is not simply a place to sleep at night, but a place to spend time creating, tweaking, and making one’s own. These acts are not always logical extensions of life, but sentimental realities that the logical Fuller overlooked when creating his grand plans for the Dymaxion House. '''Fuller did not understand that maintaining a home in many ways is a labor of love''', outside the need for efficiency and logical order. In a sense, the Dymaxion “Dwelling machine” solved issues and inefficiencies that people didn’t want fixed. | While Fuller certainly saw and understood many problems of the future of housing, such as energy and water consumption, inefficiencies of space and raw materials, and excessive upkeep requirements, he failed to understand the purpose of a house as a home. The cold, specific and deliberate nature of the Dymaxion House left little input for the dwellers, who were more fulfilling the requirement of inhabitant rather than homeowner, seen as simply another machine expected to act in a logical manner within the environment. Having such a well thought out dwelling was a drastic shift from the organic standard of homemaking, failing to fully realize that the purpose of home is not simply a place to sleep at night, but a place to spend time creating, tweaking, and making one’s own. These acts are not always logical extensions of life, but sentimental realities that the logical Fuller overlooked when creating his grand plans for the Dymaxion House. '''Fuller did not understand that maintaining a home in many ways is a labor of love''', outside the need for efficiency and logical order. In a sense, the Dymaxion “Dwelling machine” solved issues and inefficiencies that people didn’t want fixed. | ||

Revision as of 21:26, 9 December 2008

DYMAXION = DYnamic + MAXimum + TensION

Contents

BUCKMINSTER FULLER

[Read Up. The Man, the Myth, The Legend]

Buckminster Fuller was a man of no formal training as a physicist or architect who nevertheless had a revolutionary and lasting impact on both fields. Infamously charismatic, Fuller decided to make his existence on earth:

"a lifelong experiment designed to discover what-if anything-a healthy young male human of average size, experience, and capability with an economically dependent wife and newborn child, starting without capital or any kind of wealth, cash savings, account monies, credit, or university degree, could effectively do that could not be done by great nations or great private enterprises to lastingly improve the physical protection and support of all human lives, at the same time removing undesirable restraints and improving individual initiatives of any and all humans aboard our planet Earth"

In his pursuit of this lifelong goal, Fuller created many novel and pragmatic alternatives to modern dwellings, modes of transportation, urban layouts, and more. R. Buckminster Fuller based his designs on the principle that resources on earth are abundant enough to support all human life, as long as we humans can exercise the ingenuity to use everything to its maximum potential. All of his inventions are therefore his attempt to revolutionize social conception of certain practices he found wasteful. Fuller's ultimate goal was no less lofty than the preservation of mankind on earth from his own self-destruction. This desire is embodied most elegantly in the Dymaxion House.

THE STORY OF THE DYMAXION HOUSE

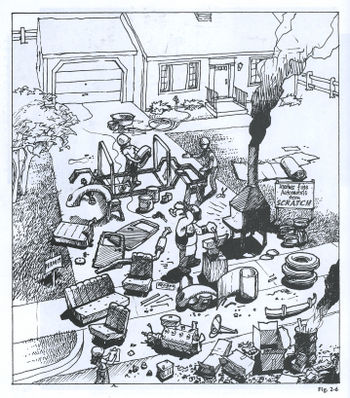

In the era of industrialized technology, Fuller found resource mismanagement inexcusable. One of the practices he most lamented was the lack of industrial production of houses. To build houses by hand, Fuller thought, was an archaic practice that was especially apparent when you compared it to the idea of building a car by hand. [INSERT PICTURE OF CAR BUILDING HERE] To construct houses out of materials considered by the general public as more sentimentally "natural," like wood, than of a material which was cheap, light, sturdy, and comparatively indestructible, like aluminum, was a gross waste of resource. Fuller considered creating such a building tantamount to planned obsolescence.

The Dymaxion House was a work that took Fuller 19 years to bring to fruition for a variety of reasons. While the initial idea was created early in Fuller’s career, the project hit many snags, and lived through many delays, before going into an anticlimactic production, which only yielded two finished houses.

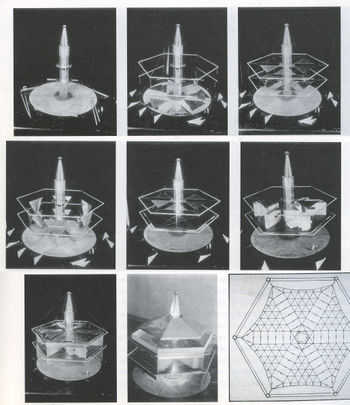

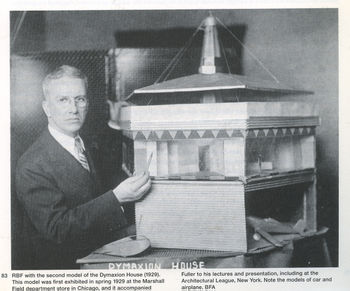

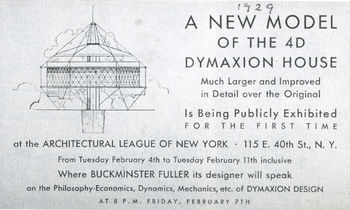

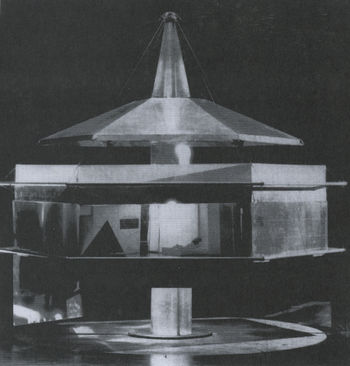

The 4D Dymaxion House

Dymaxion Deployment Unit

Dymaxion Dwelling Machine

AUTONOMY AND EFFICIANCY

cheap light and reproducible <---hangouts from social reform, goal modernity, - making home life around him systematic life at the end of the production line?

BEHAVIORAL

indiviuality within a house......

FAILURES

1. A house is a labor of love. The systematic mechanization of the home, and Bucky's incredibly futuristic outlook, ignores any past conception of what has been characterized as "homely." The common conception of "home" usually involves unforeseen additions and renovations, seemingly useless nooks and crannies that always get piled with tchotchkes and "homely" detritus. For a greater discussion of this idea of homeliness, " Thinking Beyond Today," an essay by Daisy Froud of London-based architecture firm The AOC, excellently discusses this domestic phenomenon. In a May 2008 interview with the firm, principal Tom Coward concisely explains"If something is really, really remarkable everyone will look at it and say, ‘wow!’, but they’ll be too scared to touch it, sit on it, eat it or whatever. And if you do something too commonplace it won’t get noticed. So actually the furtive approach is in that middle territory."

2. creating the most efficient house

3. needs to have a critical mass of people who are willing to sacrifice choice.

4. An excerpt of Le Corbusier's Vers un'Architectur on Mass-Production Housing

A great era has just begun.

There exists a new spirit.

Industry, invading like a river that rolls to its destiny, brings us new tools adapted to this new era animated by a new spirit. The law of economy necessarily governs our actions; only through it are our conceptions viable.

The problem of the house is a problem of the era. Social equilibrium depends on it today The first obligation of architecture, in an era of renewal, is to bring about a revision of values, a revision of the constitutive elements of the house.

Mass production is based on analysis and experimentation.

Heavy industry should turn its attention to building and standardizing the elements of the house.

We must create a mass-production state of mind:

A state of mind for building mass-production housing.

A state of mind for living in mass-production housing.

A state of mind for conceiving mass-production housing.

WRONG PLACE, WRONG TIME, OR THE ETERNAL PENDULUM OF POP CULTURE

One possible cause of the death, or non-implementation, of the Dymaxion House could be in fact completely divorced from the design itself, and more reliant on prevalent social and cultural attitudes of the time. One could argue that the cultural aesthetic of the United States has shifted its preference between two opposing poles, on the one hand the concept of mass homogeneity, association with "popular" culture, and a singularly unified "public," and on the other the desire for individuality and finding one's "niche." This can be seen throughout the 20th century: WWI as unity, the prosperous 20's as individuality, the Great Depression (30's), WWII (40's) and 50's suburbanization/baby boom generation all acted as unifying cultural forces, the 60's and 70's promoted individual liberty, and the ubiquity of the ubiquitous I-want-my-MTV generation in the 80's and 90's.

The failure of the Dymaxion House to popularize could simply be attributed to the cultural climate of the time and place. Fuller first publicly unveiled the design on July __, 1929, at the tail end of the [Roaring Twenties], and just months before Black Tuesday and the stock market crash. This unfortunate timing fell at the end of an affluent era, when people had the choice and money to not live in something that looks like what everybody else is living in, and just before anybody who would potentially fund or could potentially fabricate the Dymaxion House en-masse. All of the "good" qualities that Fuller touted were in fact all of the undesirable qualities of the time period.

The Failure of A House is a Labor of Love

Buckmister Fuller created a house meant for the future. In every way, the genius of Fuller looked to solve the world's grandest problems with the Dymaxion House, by creating a new paradigm for sustainable living, eventually ending in universal world harmony. In looking to create a logical, justified, and mass produced place of dwelling, Fuller looked to solve the larger societal issues which he felt faced the larger human race. The Dymaxion House is his solution to these issues, leveraging the technological and manufacturing might of a fully mechanized United States of America. Looking at the Dymaxion House from the Fuller perspective, one would think that every qualm of modern living is addressed by the overly obsessive Fuller.

In creating one of the most thought out, theoretically logical and efficient dwellings of all time, Fuller forgot basic necessities, by structurally dis-allowing the "nooks and crannys," of a true home by removing all choice and flaws from a home. In recalling one of Fuller’s presentation of a Dymaxion House, a reader of the New York Times recalls Fuller’s lack of thoughts on actual livability for the house:

DYMAXION HOUSE;Pitter-Patter On the Roof Published: May 31, 1992

In reading Witold Rybczynski's essay "A Little House on the Prairie Goes to a Museum" [ April 19 ] , I was reminded of the time in 1944 when I participated in a conference with Buckminster Fuller regarding his Dymaxion House. I attended at the request of my boss. He told me he would like to have an engineer accompany him. (I am an aeronautical engineer.) He wanted me as window dressing. Since I might feel uncomfortable if I said nothing, he advised, "You can say anything you feel like." We drove to the New Jersey Meadowlands, where we discussed the possibility of my boss financing a 500-house development. It was wonderful to hear Fuller's description of the technical achievements in his house, and the idea of a central compression column and thin curtain walls sounded extremely efficient. I realized that the three-hour conference was almost over and I had not made a single comment, so I asked: "Mr. Fuller, Grumman Aircraft gave me an employee's discount on an aluminum canoe. I like the canoe, but it isn't good for fishing because of the noise the water makes against the hollow aluminum. Would the noise on the roof be bothersome?" He laughed and said, "Well, I hadn't thought of that." On the way back to New York, I asked my boss if he was going to buy the houses, and he told me he was not. I said, "Why not? They seem so exciting." He told me it was because of the question I had asked and explained: "It wasn't your question; it was his answer. If he hadn't thought of that, I wondered how many other things he hadn't thought of."

To the Editor:

- LEONARD M. GREENE White Plains, N. Y.

While Fuller certainly saw and understood many problems of the future of housing, such as energy and water consumption, inefficiencies of space and raw materials, and excessive upkeep requirements, he failed to understand the purpose of a house as a home. The cold, specific and deliberate nature of the Dymaxion House left little input for the dwellers, who were more fulfilling the requirement of inhabitant rather than homeowner, seen as simply another machine expected to act in a logical manner within the environment. Having such a well thought out dwelling was a drastic shift from the organic standard of homemaking, failing to fully realize that the purpose of home is not simply a place to sleep at night, but a place to spend time creating, tweaking, and making one’s own. These acts are not always logical extensions of life, but sentimental realities that the logical Fuller overlooked when creating his grand plans for the Dymaxion House. Fuller did not understand that maintaining a home in many ways is a labor of love, outside the need for efficiency and logical order. In a sense, the Dymaxion “Dwelling machine” solved issues and inefficiencies that people didn’t want fixed.

The ultimate failure of the Dymaxion House is largely shared with the failed ideas of futurist modernity. While certainly the Dymaxion House found opposition to success through its own failure in the marketplace, the ideological context which it was conceived may be equally responsible for pre-fabricated housing failing to catch on in the 1930-40s.

One of the common follies of Dead Media lies around the concept of being "before its time," a device or media which looked to solve problems which were outside the everyman's needs. In looking to solve "future-issues," by fundamentally rethinking what a house was, the Dymaxison House failed to reconcile with the organic evolution of the house itself. In the wake of "New Deal" politics, Fuller himself looked to recreate the most basic of American possessions and replace it with a mass produced image of what the future required, without first considering the impetus for how the home came to be in its current iteration

Sources

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE6DD163EF932A05756C0A964958260&scp=17&sq=buckminster%20fuller%201992&st=cse - Dymaxion Letter to the editor

http://www.paleofuture.com/2008/12/tomorrows-kitchen-1943.html